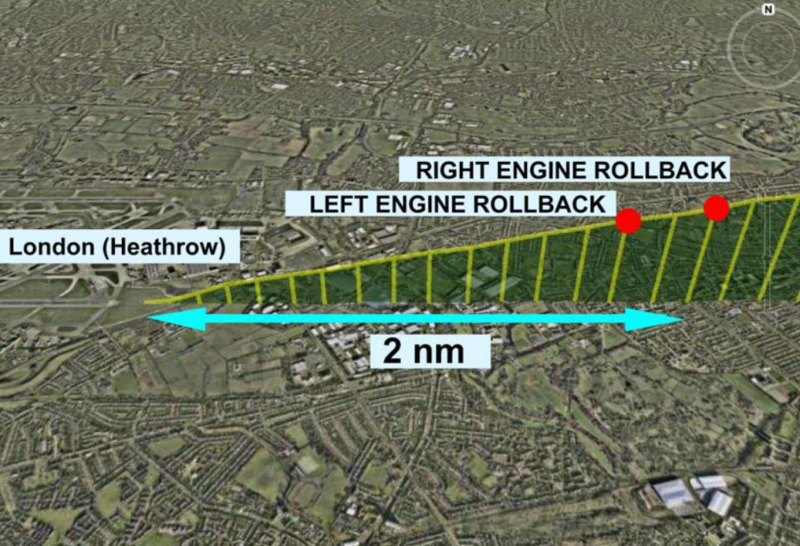

On the afternoon of January 17, 2008, British Airways Flight 38 was operating a scheduled flight from Beijing to London Heathrow. However, as the Boeing 777 approached Heathrow, both the engines gradually stopped responding to auto throttle commands to increase the thrust and instead rolled back. As a result, Flight 38 lost airspeed and struck the ground about 330 meters (1080 feet) before the runway threshold and skidded to a stop on the grass beside the runway.

Miraculously, there were no fatalities, but the Boeing 777 sustained substantial damage, marking the First Hull loss of the Boeing 777 Family.

Flight Details

The British Airways Boeing 777-200ER with registration G-YMMM was operating flight BA38 from Beijing to London Heathrow with 136 passengers and 16 crew members. Flight BA38 was under the command of Captain Peter Burkill, who had 12,700 total flight hours, including 8,450 flight hours in the Boeing 777. The 43-year-old captain was accompanied by Senior First Officer John Coward, who had 9,000 total flight hours, including 7,000 hours on this type. Also, onboard the flight was another First Officer Conor Magenis who had 5,000 total flight hours, with 1,120 hours on this type. There were also 13 cabin crew members onboard.

Due to predicted extreme coldness at the waypoint POLHO, located on the border of China and Mongolia, the flight plan for Flight BA38 required an initial climb to 10,400 m (FL341) with a descent to 9,600 m (FL315). After a detailed check of the flight plan and weather conditions, the flight was cleared to depart from Beijing. The startup, taxi, takeoff, and departure were all uneventful.

During the climb, Air Traffic Control (ATC) requested Flight BA38 to climb to an initial cruise altitude of 10,600 m (FL348), which the crew accepted. The crew further briefed that they would monitor the fuel temperature en route due to predicted low temperatures. The autopilot was set in the Vertical Navigation (VNAV) mode for the initial climb, and the Vertical Speed (VS) mode was used for two subsequent climbs to FL380 and FL400 over Russia and Sweden.

Throughout the flight, the crew monitored the fuel temperature displayed on the Engine Indication and Crew Alerting System (EICAS) and noted that the minimum indicated fuel temperature en route was -34˚C. At no time did the low fuel temperature warning activate during the flight.

Flight BA38 continued uneventfully until the later stages of the approach into Heathrow. As the aircraft approached Heathrow, the captain was the pilot flying while the first officer was monitoring. The aircraft was radar vectored for an ILS approach to Runway 27L at Heathrow and was subsequently stabilized on the ILS with the autopilot and auto throttle engaged. About 83 seconds before touchdown, at 1,000 feet above aerodrome level (aal), the aircraft was fully configured for landing, with the landing gear down and Flap 30 selected.

At around 800 feet, the co-pilot took over control of the aircraft as per the briefed procedure for manual landing. At 600 feet, the autopilot was planned to be disconnected. However, after the co-pilot assumed control, both engines received an increase in thrust command from the auto throttles. While the engines initially responded, at approximately 720 feet, the thrust of the right engine decreased, and shortly after, the thrust of the left engine decreased to a similar level. Although the engines did not shut down, they continued to produce less than the commanded thrust above the flight idle. The co-pilot observed that the thrust lever positions had started to “split” at this point, just 48 seconds before touchdown.

Clearance to Land

Upon passing 500 feet above ground level, the Radio Altimeter height automatically called out. At this point, Heathrow ATC granted the aircraft clearance to land, which was acknowledged by the crew. Approximately 34 seconds prior to touchdown, at around 430 feet over the ground, the captain declared that the approach was stable, to which the co-pilot responded “Just.”

Seven seconds later, the co-pilot noticed that the airspeed was falling below the expected approach speed of 135 knots. The flight crew could be heard on the Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR) discussing that the engines were at idle power, and they attempted to identify the reason for the loss of thrust. Despite further attempts to increase thrust from the auto throttle and manual movement of the thrust levers to fully forward, the engines failed to respond. As the autopilot attempted to maintain the ILS glide slope, the airspeed continued to decrease.

First Office: It’s not giving me power. What going on?

Captain: What do you mean?

First Officer: It looks like we have double engine failure.

As the airspeed reached 115 knots, the ‘Airspeed Low’ warning and a master caution aural warning were annunciated. Although the airspeed stabilised briefly, the captain decided to retract the flaps from Flap 30 to Flap 25 in order to reduce drag. However, the airspeed continued to decrease and had fallen to approximately 108 knots by the time the aircraft had descended to 200 feet.

Ten seconds before touchdown, the stick shaker operated indicating an imminent stall. The co-pilot responded by pushing the control column forward, causing the autopilot to disconnect and reducing the aircraft’s pitch attitude. In the last few seconds before impact on the ground, the captain attempted to start the APU and transmitted a ‘MAYDAY’ call upon realizing a crash was inevitable.

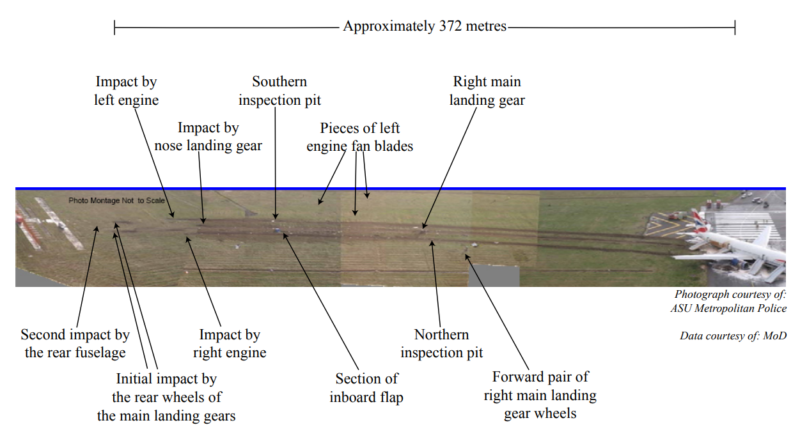

As the aircraft approached the ground, the co-pilot pulled back on the control column. However, the aircraft struck the ground in the grass undershoot for 27L, approximately 330 metres short of the paved runway surface and 110 metres inside the airfield perimeter fence.

Evacuation and Injuries

The aircraft came to rest on the threshold markings at the start of runway 27L. The captain attempted to initiate an evacuation by making an evacuation call. However, he inadvertently transmitted the call on the Heathrow Tower frequency, believing it to be on the cabin Passenger Announcement (PA) system. In the meantime, the F/O started the evacuation checklist. After the tower advised that the call had been on the tower frequency, the captain repeated the evacuation call over the aircraft’s PA system. After completing the evacuation checklist, the flight crew left the flight deck and exited the aircraft through the escape slides at Doors 1L and 1R.

Emergency services quickly arrived on the scene, and all passengers and crew members evacuated the aircraft via the slides. One of the passengers received a serious injury, a fracture of his right leg, due to parts of the right main landing gear penetrating the cabin. Furthermore, 34 passengers reported minor injuries, principally to their neck or back and 12 of the 13 cabin crew members suffered minor injuries.

Aircraft Damage and Findings

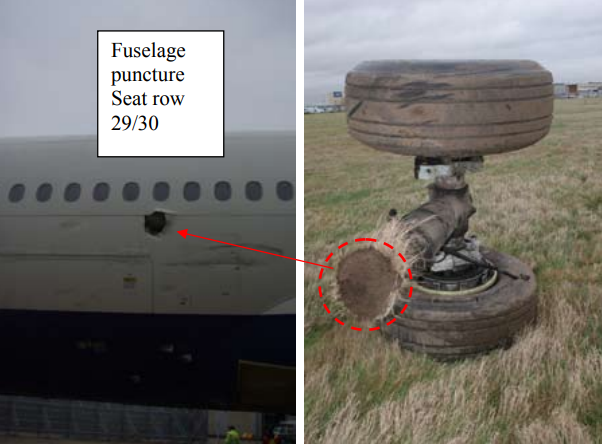

During the impact and short ground roll the nose landing gear and both the main landing gears of the Boeing 777 collapsed. The right main landing gear separated from the aircraft but the left one remained attached. The right landing gear’s forward truck beam and its wheels had punctured the right side of the fuselage adjacent to seat rows 29-30, at the height of the seat armrest.

The nose landing gear had separated from the aircraft; damage to its attachments were consistent with both a high vertical load and side load to the left.

Despite suffering heavy damage, both engines remained attached to the aircraft. Both engines had suffered heavy damage to their undersides and cowlings caused by the ground slide. The left engine had lost its accessory gearbox, while the right engine gearbox only remained attached by some of its pipework.

A further investigation found that both engines had ingested considerable quantities of earth and debris which had damaged the fan blades. The left engine was more badly damaged, having lost approximately 50% of the span of each blade as the engine had struck a concrete drain during the ground slide.

Even though around 6,750 kilograms (14,880 lb) of fuel leaked from the engine, thankfully no fire started. The fuel continued to leak from the engine fuel pipes until the spar valves were manually closed. The investigation didn’t find any signs of fire or non-containment on either engine nor any damage which could not be explained by the impact.

There were no fatalities, but the Boeing 777 was declared the First Hull loss of the Boeing 777 Family and was subsequently written off.

The investigation into the accident was led by the UK Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB). The investigation found that the accident was caused by ice crystals in the fuel system that restricted the flow of fuel to the engines. The ice crystals were formed due to a combination of low fuel temperatures and high altitude as Flight BA38 flew a route that crossed Mongolia, Siberia, and Scandinavia, at altitudes between FL348 and FL400, in temperatures between −74 °C (−101 °F) and −65 °C (−85 °F).

As a result, small quantities of water in the fuel formed ice crystals which restricted fuel flow to the engines when thrust was demanded during the final approach to landing.

The AAIB investigation identified the following probable causal factors that led to the fuel flow restrictions:

- Accreted ice from within the fuel system was released, causing a restriction to the engine fuel flow at the face of the FOHE, on both of the engines.

- Ice had formed within the fuel system, from water that occurred naturally in the fuel, whilst the aircraft operated with low fuel flows over a long period and the localised fuel temperatures were in an area described as the ‘sticky range’.

- The FOHE, although compliant with the applicable certification requirements, was shown to be susceptible to restriction when presented with soft ice in a high concentration, with a fuel temperature that is below -10°C and a fuel flow above flight idle.

- Certification requirements, with which the aircraft and engine fuel systems had to comply, did not take account of this phenomenon as the risk was unrecognised at that time.

Aftermath

Based on the findings of the investigation, the AAIB made several recommendations to improve flight safety. These included improving the design of fuel systems to prevent the formation of ice crystals, providing better training for flight crews to deal with unusual engine responses, and improving the monitoring and display of engine parameters during flight.

British Airways immediately took steps to improve the safety of its fleet, including implementing new procedures for fuel management and engine monitoring. The airline also worked closely with the manufacturer and other industry partners to address the issues identified in the investigation and to improve the safety of its aircraft.

All 16 crew members of Flight BA38 were awarded the BA Safety Medal for their performance during the accident. The medal is British Airways’ highest honour. On 11 December 2008, the crew members also received the President’s Award from the Royal Aeronautical Society.

Following the incident, eighteen Safety Recommendations have been made. The investigation and subsequent recommendations have contributed to improving aviation safety and preventing similar incidents from occurring in the future.

Feature Image via Twitter