Contributed and written by reader Bryan Cunningham

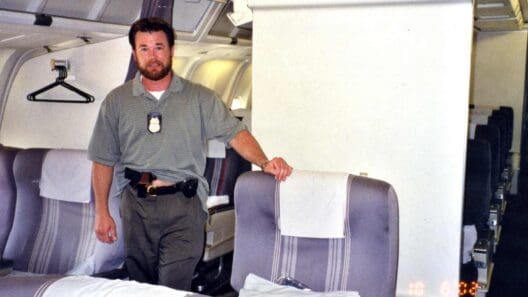

At the time of my accident, I was an Aircraft Technical Representative for a US based airline in the Technical Operations department stationed in Central America. A few weeks each month, I would fly down to El Salvador with a few other crewmembers; together we would oversee heavy maintenance work done on Airbus A320s by Aeroman, an aircraft Maintenance Repair Organization (MRO).

On May 30th 2008, I was finishing up my latest stint at Aeroman in San Salvador and I was looking forward to taking a few days off. I was headed to neighbouring Honduras, to visit my son who was four years old and was living with his mom.

I love El Salvador but I was eager to get away and spend time with my son William, who I hadn’t seen in a couple months. That Friday morning I called TACA and switched from an afternoon to a morning flight, TACA 390.

Not a good choice. In fact, it was the first of many decisions I would make that changed the fate of that day.

When I arrived at the airport in San Salvador and checked-in for my flight to Tegucigalpa, the capital and biggest city in Honduras, I was given a choice to sit in the middle of the plane or move to the back. I chose row 26.

That was a good choice.

Like an Ashtray

Toncontin International Airport, TGU, is unlike any airport you’ve seen before, there’s no city that comes close. It’s one of the world’s most dangerous airports. The site has been described as “like an ashtray”, use your imagination. It’s basically a runway set in a basin surrounded on all sides by steep hills, it’s so small and such a tight squeeze that every approach is a challenging one for pilots. I’ve flown in there many times over the years, but I’m still not used it.

(Click to see a “normal” landing at TGU on YouTube)

The flight that morning was uneventful, 131 miles in an A320 over the rainforest and mountains of Central America. The flight is normally 40 minutes, but it took a little longer that morning because the pilot had to make a go-around. Tropical Storm Alma had just swept through the country and the weather over Tegus, as it’s nicknamed, was not the best.

We made a second go-around.

It’s common for pilots to do a second go-around there; finally, after circling for a bit, we descended. As our plane swooped in, I noticed that the landing was so smooth that it felt unreal. I knew something was wrong.

In the middle of the landing, people began clapping. Everybody was cheering! But I looked out the window, to my left, and I noticed that we had passed a set of markers that indicate that we were approaching the end of the runway. In that split second when I felt something was wrong; I pulled my seat belt tighter, threw up my arms and braced for impact. I knew we were going to hit something.

Within milliseconds, it happened.

Cracked Open Like an Egg

It was a lucky thing I moved to row26 and wasn’t in the middle of the plane, where I was originally seated. As the jet slammed to a stop, it cracked open like an egg. Light came shining through into the cabin around row 10. The plane had buckled right across the middle, as it came to rest on a hillside just beyond the end of the short runway.

The official investigation unfortunately claimed pilot error, but from my perspective three factors doomed our flight: the runway was slick after Tropical Storm Alma, there was heavy fog and we probably hit the ground too far down the runway to ever stop safely.

One-hundred-forty people hit seatbacks and tray tables like dominos. Then the pandemonium began. People were screaming, shouting “fire!” and pushing their way to escape.

Later, we learned that the captain had died upon impact. In total, 5 people died. 3 in the aircraft and 2 were in a taxi on the ground that got crushed by the impact of the aircraft.

Back in the cabin flight attendants were doing an excellent job helping people get out, despite the chaos. They carried out their emergency procedures very well. I was lucky to be in the back and one of the first people to head down the emergency slide. From outside the plane, I could see fuel leaking and thought about the possibility of an even bigger fire.

There were so many people coming out of the plane needing help. I didn’t think twice about grabbing some elderly passengers and pulling them up the small hill that we’d come to come to rest below. From there we watched the last few passengers stream out of the wreckage, as crowds gathered to witness the mess.

Ambulances arrived quickly and police were on the scene a few minutes later, with a triage unit being set up in the meantime. Every person who got out alive had minor injuries, except those in the middle. They were pretty hurt. I was in a lot of pain, but fortunately it was only some bruises. I knew most people were a lot worse off than I was and I wanted to make sure they were taken care of first.

I wanted to call my family right away, but I couldn’t remember any phone numbers. They wouldn’t have been much use anyway, since I left my phone and everything but my passport and credit cards on the plane.

As I stood there among all the chaos, I was in disarray. I was confused and didn’t know what to do, I was still in shock. Out of the blue, a woman who works for the airport came over to me. Out of everyone standing around, she somehow grabbed me. She brought me over to her office, where I was able to use a phone and call my colleagues in San Salvador. They gave me all the local numbers I needed to sort myself out to call my family and friends.

At that point, I was looking pretty dishevelled and didn’t know what to do. The woman from the airport was kind of enough to bring me to my hotel. When I got there, I had messages waiting from my company and the US Embassy. I didn’t think anyone would know I had been in the crash, but I guess news travels quickly!

It was clear my pain was getting worse, so I got a ride to the hospital where most of the foreigners on flight 390 had been taken (people were split up in between three or four hospitals). I stayed there a few hours, before doctors verified that there was nothing major wrong with me.

In the hospital I couldn’t help but look around and fixate on those people worse off than me. Some had bandages around their heads or patches on their eyes. Some were in wheelchairs with broken legs or feet.

Truth be told, it felt awful to be the one who was OK. Classic survivor’s guilt. But I also felt really lucky, it just wasn’t my time yet.

I stayed in Tegus for four days; happy to be alive, replaying that day in my head. When it was time to leave, Taca bussed me and others four hours north, not a bus ride I want to repeat, to flights in San Pedro Sula. Imagine twisty Central American roads, to your left, for mile after mile, the road falls off suddenly into deep ravines. From San Pedro Sula, I hopped a flight home to Miami.

TGU remained closed to large jets for a long time. Big planes were forced to divert 40 miles north to an air base with long runways until the investigation was finished. There is a lot of debate going on in Honduras about whether the airport should close forever. Flight 390 was just the latest in a string of deadly accidents there at the time.

The crash of Taca 390 was quite an experience. Working in the aviation field, it seems ironic to have been in a crash in a plane I know so well and on an airline I’ve worked with for such a long time in San Salvador.

In a word, it was surreal.

Contributed and written by reader Bryan Cunningham

Wow. Seems the passengers on the plane were safer then the guys in the taxi outside the plane.

Holy Cow! Sam, I didn’t know you survived a plane crash. Watching the YouTube video provided, I couldn’t help but notice the short runway.

Glad you are still around!!

This is a story contributed by reader Bryan Cunningham. I was not on this flight.

tegoose has always been waiting for the next overrun accident to happen. Unsafe is perhaps the mildest critque possible- perpetually dangling on a cliff is another. Not so unsafe coming in over the road, not the ski-slope approach so wonderfully done by American Airline 757, but, no approach ought to be standard when passing over the angled ski-slope just seconds before confronting the runway and the white warningstripe. . Blown tires, overheated brakes, major league angst in the cockpit and the passenger areas. What to do? so , every once in a while the airport trashes another 737 or airbus or something else? Hire the engineer that can remove the ski-slope by removing many , many truck loads of dirt, and keep going backwards, until we have a safer runway approach. Carve out that hill, move the dirt, damn the cost, and then be satisfied and a bit safer. Or, junk the airport and use the nearest safe runway,,and listen to everbody grumble about the distance . There is only one pilot, not the captain, left to blame , but given the conditions, perhaps the alternate was the wiser choice.The bus trip is like Gatwick to Heathrow without the charm-roads overlooking a steepfall.

I’m happy to hear that you made it out alive. God bless you and the people of flight 390.

Sam…

Excellent idea to pass along an account of an aviation accident written by a survivor, especially one who is part of the industry.

It must have been especially troubling for him, because he knew things were going bad as events were unfolding.

Thanks for passing this first person account along.

John Gillan

Illinois, USA