Lebanon’s national carrier, Middle East Airlines, known as MEA, operates a modern fleet of Airbus jets throughout the area and to cities across Europe, with a handful of long haul routes to West Africa. It is a byword for good service and reliability, and is a member of the SkyTeam alliance. During the civil war of the 1970s and 1980s, Lebanon was one of the most dangerous places in the world, and MEA became a vital link in the survival of the country. Here is a story of an airline that wouldn’t stop flying no matter how great the obstacles, of bravery virtually unmatched in the history of civil aviation.

Lebanon, a tiny republic on the Mediterranean coastline, was a province of Syria until 1920, albeit with a distinctive cultural identity that reaches back millennia into the pages of the Bible (which is even named after the Lebanese coastal town of Byblos, incidentally). Fully independent in 1948 after the end of the French mandate in the region, Lebanon reasserted itself in the role it had occupied since the dawn of time, as a natural crossroads for trade and transport, located on the eastern edge of Europe and the western edge of Asia, now newly-rich with oil wealth. Its vibrant capital city of Beirut became famous in the early years of the jet age for its banks, nightclubs, markets and beaches, with roads leading up into the Lebanon mountain range, whose snowy peaks provided a dramatic backdrop to the bustling city. Only in Lebanon, it was said, could a person water ski in the morning and snow ski in the afternoon.

The national airline, Middle East Airlines, grew quickly with fleets of Vickers Viscounts, deHavilland Comet 4s, Vickers VC-10s and Sud Aviation Caravelles. The first Boeing 707/720 arrived on January 1, 1966, in the form of Ethiopian Airlines’ Queen Of Sheba on a 22 month lease. In November 1967 it was swapped out for sister ship The Blue Nile, which was written off in a non-fatal landing accident on January 9, 1968. In fact MEA’s choice of jet airliner was the VC-10, but British banks refused to finance the purchase, so MEA turned to the United States instead and brand new 707s were soon arriving from Seattle.

Beirut has always been a noisy city, with the blare of car horns, the muezzin call to prayer echoing from mosques, the bark of competing souk traders, the tinny sound of Arabic music and preachers sermons coming from tinny speakers. MEA’s deafening and smokey Comet 4s and 707s fitted right in roaring overhead at just fifteen hundred feet on finals for the airport which is just a few miles to the south of downtown. By 1970 there were more than 100 daily flights, including the likes of Varig and Japan Air Lines, and Pan Am stopped every day in both directions on its round-the-world jet service.

However, beneath the surface of Lebanon’s jet set idyll lurked political faultlines. Lebanon, four million people in a coastal sliver half the size of Wales, was home to 17 government-recognised religions, who did not always get along, and who were not equally represented in the lopsided constitution bequeathed by France. On top of that, Palestine, Lebanon’s neighbour to the south, had become Israel in 1948, so Lebanon was also home to one million Palestinian refugees, now stateless, including armed liberation movements who used Lebanon as a base for their paramilitary activities.

On December 26, 1968, a taxiing El Al Israeli 707 was sprayed with machine gunfire while taxiing for takeoff at Athens airport by members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), killing a passenger. Since Lebanon was the base for the PFLP, and the better-known Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) headed by Yassir Arafat, it was the inevitable target for retaliation.

On the evening of December 28, 1968, under the codename Operation Gift, Israeli commandos raided Beirut airport. Although mercifully there were no human casualties, twelve airliners were destroyed, including eight belonging to MEA – three Comet 4s, two Caravelles, a Vickers Viscount, a Vickers VC-10 on lease from Ghana Airways, and a brand-new 707 fresh from the factory in Seattle. Rival Lebanese International Airways lost all four of their fleet, resulting in the end of the airline and their route licenses being transferred to MEA; Lebanese cargo airline Trans Mediterranean Airlines lost two propliners. MEA was back up and running within a day with leased airliners from a variety of sources, but in retrospect, the attack was a clear marker for the beginning of Lebanon’s decades-long spiral into chaos.

It was possible to paper over the cracks in Lebanon’s glitzy mirrorball for a few more years, with only isolated incidents, such as one in August 9, 1973, when Israel identified an MEA Caravelle flight as having four wanted Palestinian militants onboard. The flight was intercepted by Israeli jet fighters after takeoff from Beirut and escorted to Israel; in fact the militants were not among the passengers and the aircraft was returned to Lebanon later the same day.

Another MEA jetliner made an unexpected visit to Israel a week later, on August 16. In an unconventional show of Arab-Israeli unity, a Libyan passenger hijacked an MEA 707 to Tel Aviv with 125 passengers onboard as a rather demented gesture of goodwill towards Israel. After the passengers were rescued, the aircraft was returned to Beirut.

The Lebanese Civil War

This incident may have seemed harmless but the “Paris of the Middle East” was heading for the rocks. The Lebanese civil war, which would last for 15 years, broke out in April 1975 with the outbreak of fighting initially between Palestinians and Lebanese Christians. With the mosaic of ethnic identities in Lebanon, the number of armed factions multiplied and quickly usurped basic functions of the state. The national army split along confessional lines and what had been a major hub of trade and leisure quickly became global shorthand for urban breakdown and chaos.

Three Boeing 747s were delivered to MEA just as the fighting began, but overtaken by events, two were quickly leased to Saudia Airlines. Despite the fighting in the city which quickly engulfed the harbourside hotels and downtown business district, MEA was able to maintain a semblance of normality for the rest of 1975, but the tragedy of war struck hard on New Year’s Day 1976. Cedarjet 438 to Dubai, a 720B with 66 passengers and 15 crew aboard, disintegrated in midair over the Saudi desert after a bomb exploded in the forward baggage compartment. The culprits were never found.

On June 27, another 720B was destroyed on the ground as the airport came under rocket and mortar attack from duelling factions. Passengers had deplaned but a crew member was killed and two others injured. Only a few days later, the fighting overwhelmed the ability of what remained of the authorities to secure the airport. Lebanon’s gateway to the world closed for 168 days, leaving MEA to find work as a charter carrier in other markets from a temporary base in Paris.

Soon after the resumption of flights, on June 5, 1977, a 707-323C was hijacked to Kuwait by a wheelchair-bound passenger, who was later released by the Kuwaiti authorities and repatriated to Lebanon.

Another hijacking took place on January 16, 1979, when a 707-323C was taken over by six pistol-wielding skyjackers with the intention of having a press conference in Larnaca. However, the Cypriot authorities refused landing permission for the flight, which instead returned to Beirut where the media event took place prior to the six surrendering.

A deadly event at the airport on July 23, 1979 was an exception in that it was not a deliberate act. A Trans Mediterranean Airways Boeing 707-327C freighter crashed inverted during circuits in the course of training a new batch of pilots. The training captain, flight engineer, safety pilot and three cadets all died.

The turn of the decade brought no respite from the civil war or its toll on civil aviation. On January 18, 1980, a Lebanese teenager hijacked a 720-023B, originally destined for Larnaca, to Iran to meet Ayatollah Khomeini to intercede with the Libyans to help find Lebanese cleric Imam Musa Sadr, missing in Libya. Instead, the flight returned to Beirut and the youth was permitted a press conference before surrendering. Ten days later, with the same intentions of keeping up the pressure to find Sadr, a man with his wife and four children aboard hijacked a Baghdad-bound 720B; upon landing at Saddam International, arrangements were made for the man to read a speech before giving himself up to the Iraqi police. On May 23 a flight bound for Bahrein only got as far as Amman before it was forced to land by a bomb threat (no bomb was found).

On the last day of 1981, a 720B exploded on the ramp at Beirut after the completion of a revenue flight; passengers and crew were incredibly lucky the flight was completed before the timer on the bomb was triggered.

This was the background in which MEA was trying to run profitably and regain its place as one of the world’s great airlines. As the 1980s began, new seats were installed in the 707s, and new destinations were opened, including the Tunisian capital and Yerevan in Soviet Armenia. Anticipating an end to the conflict, construction started on an enormous maintenance hangar at Beirut that could accommodate two 747s.

However, the worst was yet to come. 1982 saw a full-scale invasion of Lebanon by Israel to drive the PLO out;

Beirut was cut off from the world and the airport was closed for 115 days. Six 707s and 720Bs were destroyed on the ground, with two others severely damaged.

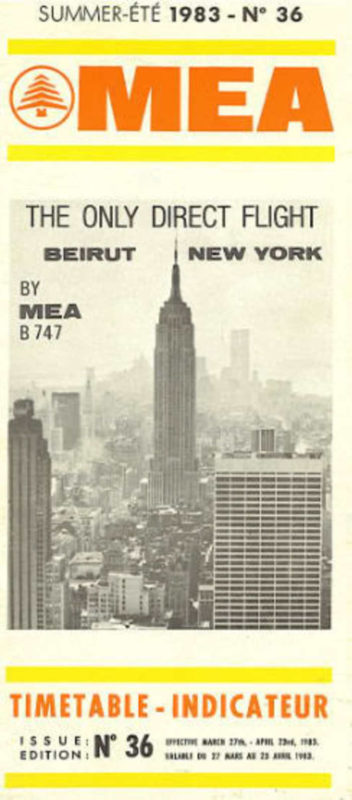

The arrival of a multi-national peacekeeping force in early 1983 led by the United States allowed for some optimism, and the two jumbos leased to Saudia returned, enabling MEA to cross the Atlantic for the first time, opening up 747 service to New York via Paris.

More Hijacks

However, on October 23, the US Marines base at Beirut airport, which in peacetime had been MEA’s training building, was attacked by a suicide truck bomber, killing 241. It was (and remains) the worst US one-day military loss of life since Vietnam. A simultaneous attack on the French military base in the city killed an additional 58. The peacekeepers soon withdrew, leaving Lebanon to its fate. Intense fighting saw the closure of Beirut airport for most of the first half of 1984 (154 consecutive days), causing losses of $46 million.

Within one hour of the airport reopening, the first Cedarjet was touching down. However, the lawless environment in which the airline operated soon reasserted itself, with a 707 near the end of a flight from Abu Dhabi to Beirut hijacked on July 21 1984 by a man with a molotov cocktail, demanding to be returned to the Emirati capital. Low on fuel, the captain was able to persuade the man to accept Beirut as a landing site, where he gave a press conference before surrendering.

When the shooting started, MEA’s executive vice-president for operations Abed Hoteit would go to the control tower and talk to inbound flights as well as aircraft on the ground waiting for start-up clearance. As soon as there was a lull in the shooting, whether of US Marines towards the Chouf Mountains immediately to the east of the airport, or from Druze or Shia militiamen towards the airport, Hoteit would let the flights come in. The airline’s policy in the case of fighting in the vicinity of the airport was that if a flight was boarded and ready to go, it was better to wait for a lull and then perform an “expedited departure” than to deboard the passengers and return them to the terminal, where they might be exposed to more danger.

MEA’s 275 pilots, all but 13 of whom were Lebanese, did not take inordinate risks. But they flew where others feared to because of their intimate knowledge of the steep mountains and narrow plains around Beirut airport, and because they regarded bringing their aircraft home to Lebanon as a national duty.

In 1984 the airline announced that it had lost $54.6 million in the previous year, and over $100 million since the start of the war. To mitigate costs, aircraft were leased out and staff took a number of pay cuts, up to fifteen percent at a time. Advertising was slashed, as no amount of persuasion could tempt travellers to visit Lebanon at war. Prestigious industry organ Air Transport World honoured founder Salim Salaam with a special award at its annual event in New York for MEA’s “persevering and surviving under very difficult conditions.”

Bad though the first decade of Lebanon’s civil war had been for MEA, 1985 was the apocalypse. At times, jet fuel could not be delivered to the airport, and the 747s proved useful as an impromptu tanker – a jumbo would be dispatched empty to Cyprus where every tank was filled to the brim, then the aircraft would tiptoe back to Beirut and the fuel would be decanted into the fleet of 707s and 720s to maintain skeleton service to the essential destinations in the airline’s route map, primarily Paris, Cairo and the Persian Gulf.

On February 23, an airport security guard commandeered an MEA 707 that had just finished boarding and was ready to call for start up at the beginning of a flight to Paris. The hijacker ordered passengers to evacuate using escape slides, but Lebanese Forces and Amal militiamen began firing and the hijacker ordered the captain to start taxiing even as the evacuation was continuing. The jet blast killed a passenger and injured others, and machine-gun fire tore a hole in the fuel tank in the left-wing. Nonetheless the aircraft took off, still with doors open and escape slides hanging. The motivation for the hijacking was to obtain better pay for airport security staff and in protest at the high cost of living. After landing in Larnaca in Cyprus, a phone call with the hijacker’s supervisor promised amnesty and an investigation into the financial claims. Upon the return of the aircraft and hijacker to Beirut, the aircraft was met by an airport authority vehicle and he was free to return to his home in the airport suburbs. Just another day in lawless 1980s Lebanon.

On April 1, a hijacker took over a 707 en route to Jeddah with claims of having a gun and a bomb and demanded Lebanese government assistance for guerillas fighting the Israeli occupation of southern Lebanon. Placated by the crew, the aircraft landed at its destination and the hijacker was arrested by the Saudi police on arrival.

On June 11, an Alia Royal Jordanian 727 was commandeered by five Shiite Lebanese armed with machine guns and explosives just before takeoff from Beirut at the start of the short flight back to Amman. They demanded to be flown to Tunis but lack of fuel required a stop in Larnaca; when Tunis refused landing permission the flight landed at Palermo. From Palermo the aircraft returned to Beirut, refuelled again, and took off, this time spending two hours on a flight to nowhere, and landed in the early hours of June 12 back at Beirut. All aboard evacuated and the aircraft was destroyed by explosives. Just hours later, a Palestinian man took over an MEA 707 that had just landed from Larnaca and demanded to be flown to Amman. After allowing the passengers and cabin crew off, the flight taxied out past the still smoking wreck of the Alia 727 and flew to Jordan where he was arrested by Jordanian authorities.

TWA Flight 847

Two days later, on June 13, one of the most famous hijackings of the era took place when TWA flight 847 was commandeered after takeoff from Athens on a flight routing Cairo-Athens-Rome (where it was to feed a transatlantic jumbo bound for Boston and Los Angeles). The hijackers were members of Lebanese Shiite groups Hezbollah and Islamic Jihad and armed with grenades and guns. The Boeing 727 stopped first in Beirut where 19 passengers were exchanged for fuel, then Algiers where another 20 passengers were released. The aircraft made two more return trips to Algiers before the remaining 40 hostages were taken from the plane and held in a prison in the suburbs of Beirut. After two weeks in captivity, they were released after one of the main demands of the hijackers, the release of 700 Shia Lebanese held in Israeli prisons, was met. Tragically, a US Navy diver on the TWA flight was killed in the course of events by the hijackers.

MEA suffered collateral damage from the TWA 847 ordeal when members of the transport workers union at New York’s JFK refused to service MEA’s 747 flight (the union leader announced “We do not work for the convenience of terrorists”), and on July 1 President Ronald Reagan announced the Lebanese flag carrier was banned from US airspace. In August MEA flew a TWA crew to Beirut to pick up their stranded 727, N64339, and ferry it to the United States for an overhaul and return to service; that was the end of the incident but Lebanon’s civil aviation sector was in tatters. As a brutal footnote to an awful summer, on August 21, a pair of 720Bs were destroyed on the ground in Beirut by fighting.

The civil war still had years left to run; on January 8, 1987, a 707 was destroyed by shelling just after 126 passengers had deplaned. On February 1 the airport closed for another protracted period of fighting, this time lasting 107 days.

In the late 1980s, the security situation on the ground in Lebanon was so depleted that airline passengers could no longer reach the airport from the eastern suburbs of Beirut or from the north of the country and faced long ferry rides from the ports of Tripoli and Jounieh to pick up flights out of Cyprus, or a long drive to Damascus airport in Syria, which included routing through the Bekaa Valley which as a result of the war had become one of the most dangerous parts of the country.

To bridge the divide, MEA began a double daily air shuttle from Beirut to Kleyate Airport (KYE/OLKA), a mostly disused military facility near the city of Tripoli in the north of the tiny country. The distance between the two airports is just 60 miles (96 kilometres) and the flight time was about fifteen minutes. The morning rotation was numbered Cedarjet 1 & 2, and the evening rotation was Cedarjet 3 & 4. As well as connecting airline passengers, locals used the flights to get from one side of Beirut to the other to get to work or to see friends and family on the other side of the divided city.

After fifteen years of fighting, negotiations between the warring factions resulted in compromise on constitutional issues, bringing the war to an end in October 1990.

150,000 Lebanese had died, including 40 MEA employees. 12 720s and three 707s were destroyed. No corner of the country was unscarred.

MEA’s vintage Boeings, having provided an essential lifeline from Lebanon to the world, now performed their final act, the conduit for the economic boom of the post-war peace dividend. Lebanese citizens who had fled abroad began returning to reclaim property and restart businesses; construction engineers and salespeople poured in to assist the mammoth rebuilding effort; and tourists were drawn by the sandy beaches, ancient culture, and cool mountain heights which now had an extra layer of notoriety.

The surviving fleet of 707s and 720s were flown round the clock as passenger numbers spiked, retirement dates repeatedly postponed. The last two 720Bs, OD-AGB and -AFM, were mostly active for crew training and ad hoc equipment substitutions but returned to scheduled service in June 1994; -AGB, built in 1960, was at the time was the oldest flying jetliner in the world. These two brave soldiers finally left Lebanon in December 1995 for new lives at Pratt & Whitney Canada as flying testbeds. MEA expanded back into old markets and, with its 747s back home again, opened up new long-haul flights to Sydney via Singapore and Sao Paolo via Dakar.

Leased Airbus A310s gradually forced 707s off the most prestigious routes to Europe where new noise legislation punished older hardware with punitive landing charges, and the last MEA 707 destinations were in the Persian Gulf and closer to home, on short one hour hops where fuel burn mattered least, such as Cairo, Amman, Larnaca and Istanbul.

Airline enthusiasts who wanted to fly on a 707 turned up regularly on MEA flights in the 1990s, but the airline still saw itself as a top airline brand and took no pride in being the last mainstream passenger 707 operator; in the timetable, the new Airbus A310s were denoted as “Airbus A310”, whereas the 707s were at best “Boeing” or sometimes just “Jet”. That aside, Lebanese of all tribes take great pride to this very day in the lifeline their national carrier provided. The survival of their nation depended on it, and MEA never let them down.

Cover Image: RABIH MOGHRABI/AFP via Getty Images

Great story. Congratulations! I have flown with MEA to Beirut some years ago and when I was on the Lebanese capital, Hezbollah creates a diversion that closes the airport for a moment, just when a A330 from Air France was preparing to land, with the French Ambassador on board. French authorities managed the situation dramatically, and gave instructions the the crew to wait for new instructions, until the made an emergency landing in Damasco, by night and without lights on track. The plane touch the ground almost empty of gas. And to leave Damasco, back to a safer airport, in Chipre, Air France must paid in cash for refuel, but crew haven’t money enough for that. Then, the crew start to ask money from business class passengers, but they where not successful: rich passengers don’t have cash, only credit cards, where no allowed to pay to refuel. So, the solution was found in economy class, where all the pocket money collected was enough to allow the plane to fly to Chipre, where the AF-A330 and all the passenger remains some days. Meanwhile, Beirut Airport never closed the operations, and all the other flights continued to arrive and depart without problems. Finally, when the AF-A330 arrives in Beirut and all this surreal story became public, it was a shame for French authorities. Three days later, France send to Lebanon they Minister of Foreign Affairs, to apologize for the ridiculousness of this situation. What was even more ridiculous…

Wonderful article that brought back some nice memories. I have flown the old (1970’s) and the new MEA and I am happy to say it has always been a pleasure. I have flown on their B707’s, B720’s and now the 320’s. Just like the country, the airline is a struggler and I wish them the best.

Impressive retelling! I have flown MEA over the years and am happy they’re survivors.

MEA what memories. My first flight in a Viscount OD-ADE 9th October 1959 I was 4 years old details from my BOAC junior Jet club log book.Can’t read the Captains name though. When I eventually had the privilege of signing these books I always put my name in capitals ! First flight on a Comet 13/7/61 OD-ADQ Beirut-Rome. Caravelle OD-AEF 13/2/64 Beirut-Rome.

We lived in Kuwait so for our holidays back to the UK we would go via Beirut then on to Rome to see my maternal Grandparents then on to the UK to see my paternal grandparents. The flights were my highlight though.I remember my parents saying how good the service was compared to Alitalia and BEA..

Nice bio on MEA! I was in Beirut for nine years as a kid. Remember the excellent viewing deck at the airport, ME DC3s, Viscounts, Comets, the first BOAC VC10 arrival, Caravelle touch and goes….. The approach into BEY went right over our apartment.