As the world wide grounding of the 737 MAX continues, and certification set-backs keep piling up, Boeing has made the decision to suspend production of the type from January 2020.

The decision, which was made at a two-day board meeting, comes after the Federal Aviation Administration refused to allow the 737 MAX to return to service in 2019; resulting in a massive blow to Boeing who was hoping to see things move faster.

The last time production of the 737 stopped was in 2008 during a 57 day work strike, however this announcement makes it the first time the company has intentionally halted production since 1997.

Throughout the grounding, which begun in March after the second 737 MAX crash, Boeing has been producing the 737 MAX at a reduced rate of 42 per month and now has over 400 in storage around the world.

Issued in a press release, Boeing maintains that this decision is the right one and notes that their priorities are: a healthy supply chain and production system, employee status and customer support.

The 12,000 employees working at Boeing’s Renton 737 MAX factory will be assigned to other 737 related work, in the Puget Sound area.

Boeing has not provided any details on how long they will be suspending production for; the Federal Aviation Administration has declined to comment on the manufacturers business decision.

Instead, Boeing has decided to focus on delivering the 400 stored frames once the grounding is lifted; however it remains unclear how long this will take, especially with post-storage checks and maintenance.

The Federal Aviation Administration says they are continuing to work with other regulators around the world, to preview and comment on proposed changes to make the aircraft safe to fly again.

“Our first priority is safety, and we have set no time frame for when the work will be completed”

Federal Aviation Administration (via Reuters)

Financially, the announcement is now expected to put a dent in the United States’ economy; as well as further damage the manufacturer’s already sore bottom line.

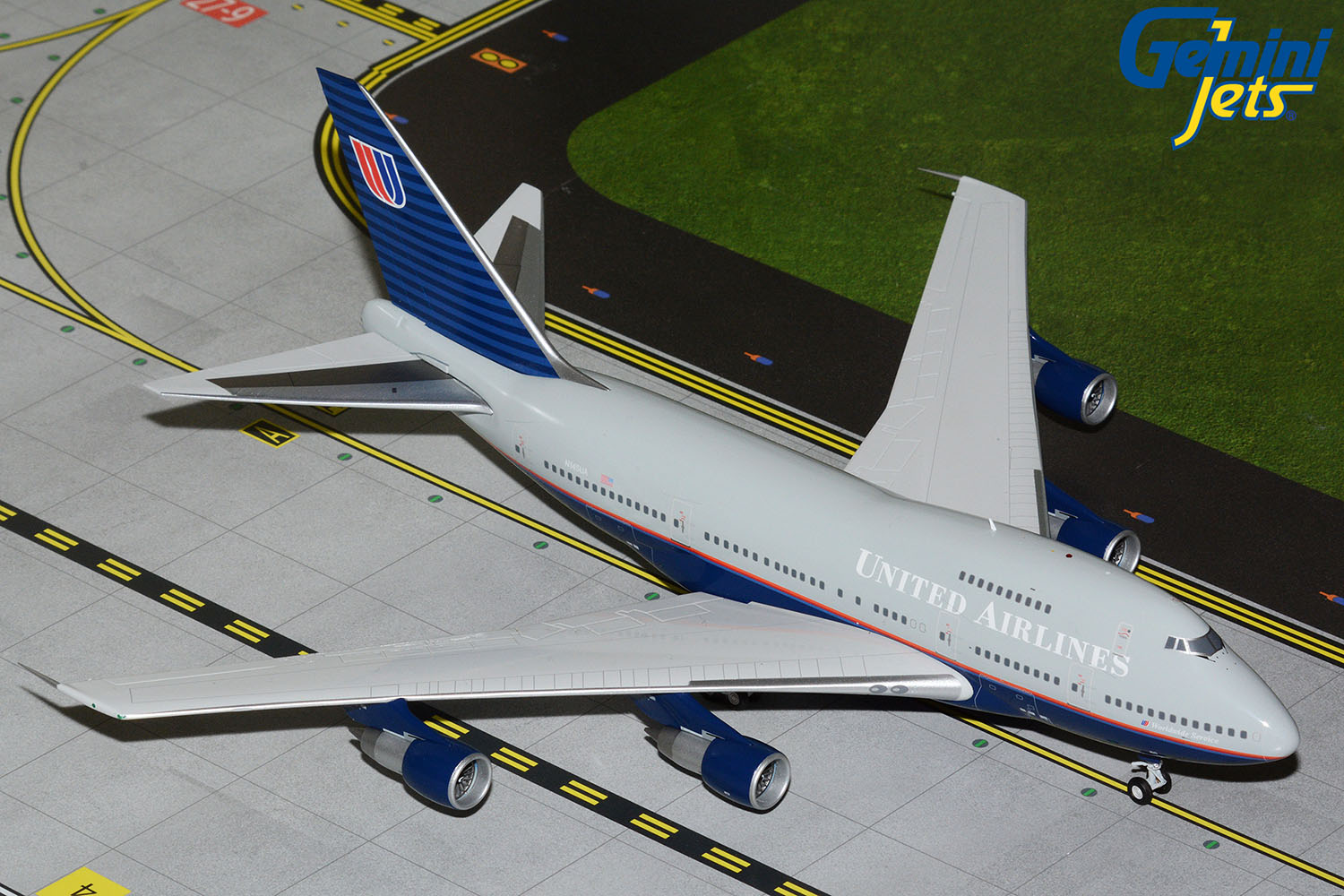

The 1997 suspension of 737 and 747 production, due to production problems, left Boeing dealing with a massive bill, according to Reuters, and the same is expected to occur with the 737 MAX.

Boeing said that they will be outlining the remaining 2019 financial results in their fourth-quarter reports in January.

Due to the specialist and small components suppliers are responsible for, they will be feeling the pressure just as much as Boeing, if not more, especially with production closure and potential re-opening in close proximity.

Boeing shares closed down 4 percent on Monday and fell 1 percent after hours, whilst Spirit AeroSystems, Boeing’s largest supplier, closed down 2 percent.

Spirit has already initiated talks with Boeing, to work with revised production plans and retain a healthy balance of production backlog and supply for a resumption.

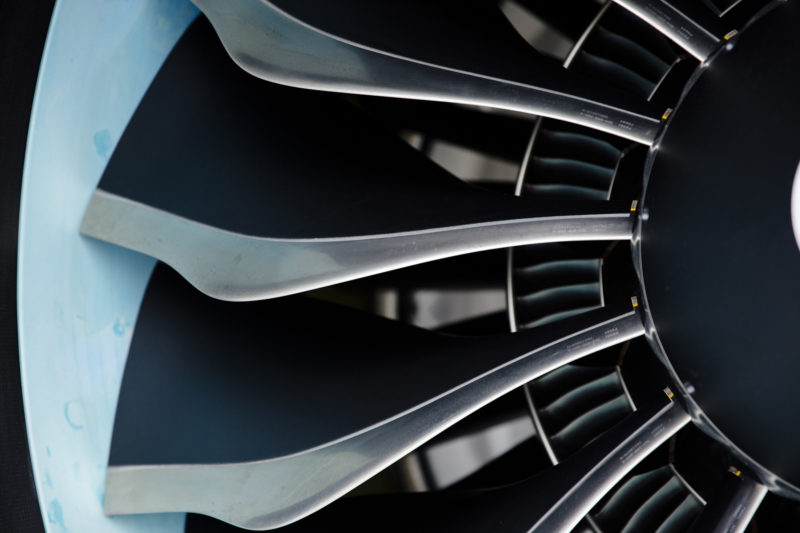

Engine manufacturer CFM International, who is a joint-venture between General Electric and Safran, will be working closely with Boeing; as engine manufacturers don’t generally receive full payments until aircraft are contractually or physically delivered to customers.

Airlines who have the 737 MAX in their fleets already are assessing their schedules and will likely have to push back their services some more, following months and months of announced network changes.

In terms of compensation, some airlines have reached preliminary or full agreements with Boeing; whereas some are still in the negotiating process. It is understood that Southwest Airlines has reached an agreement, to cover a portion of a projected $830 million hit to their 2019 operating income.

Analysts from various media outlets suggest that the aircraft won’t be given the green light until mid to late February 2020, with some suggesting even as far as March or April.

Whether Boeing gets the green light at these times or not is subject to approval from the Federal Aviation Administration and legal proceedings. Other regulators around the world have insisted that they conduct their own assessment of the aircraft, after losing their trust with the Federal Aviation Administration.

why hasnt mullenburg and all his cronies been SACKED ? they have collectively killed 346 people for christs sake , if that bunch had shot them all to death they would all be up on murder charges , so why arent they ?????