France has a long history at the cutting edge of aviation (fuselage, pitot, aileron are all loan words from French), and scored a couple of big hits at the start of the jet age with the Sud Aviation Caravelle, a twin-engined short- and medium-haul airliner which sold 282 airframes (including 20 to United Airlines) between 1958 and 1972, as well as the Nord-262 propjet which sold a respectable 110 airframes. The Dassault Mercure should have been the next big thing, but despite being popular with pilots and passengers, became a cautionary tale and fascinating footnote to the A320 family which it greatly resembled in except that one sold more than 10,000 aircraft and the other barely sold more than ten. (The correct answer is eleven – one prototype and ten production Mercures.)

Dassault Aviation’s history dates back to 1929 with impressive achievements in building military planes (most notably the Mirage jet fighter), as well as a prolific electronics division which produced radar, missile guidance, and avionics. Success with the Mystere-Falcon business jet led to the unfulfilled Mystere 30 project, a regional jet that would have seated up to 56 passengers. A 1965 market study revealed 3,250 city pairs in Europe and North America served by 210 airlines would require 1,500 short haul jetliners, and so it was decided to build a 150 seat airliner for what was obviously a huge market sector.

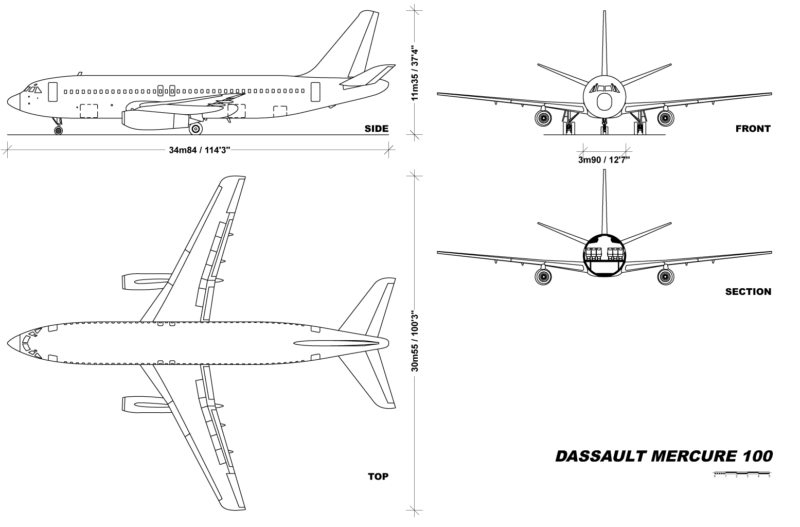

Dassault considered a range of configurations and settled on a Pratt & Whitney JT8D under each wing, superficially similar to the contemporary Boeing 737-200 although slightly bigger and heavier – the wingspan was two metres (seven feet) wider, the fuselage was four metres (14 feet) longer, and the empty weight was 2,160 kilograms (4,600 pounds) heavier. Dassault were world-renowned for their wing architecture and the new jetliner sported a sophisticated 25-degree wing sweep with leading edge slats and triple-slotted trailing edge flaps for safe low speed approaches, designed using state-of-the-art computer technology.

The name Mercure was chosen because, in the words of Marcel Dassault, “Intending to use the name of mythological god, I found only one who had wings on his helmet and ailerons on his feet.” A full-scale mock-up was displayed in June 1969 at the Paris Air Show, giving the world a glimpse of the new French jetliner.

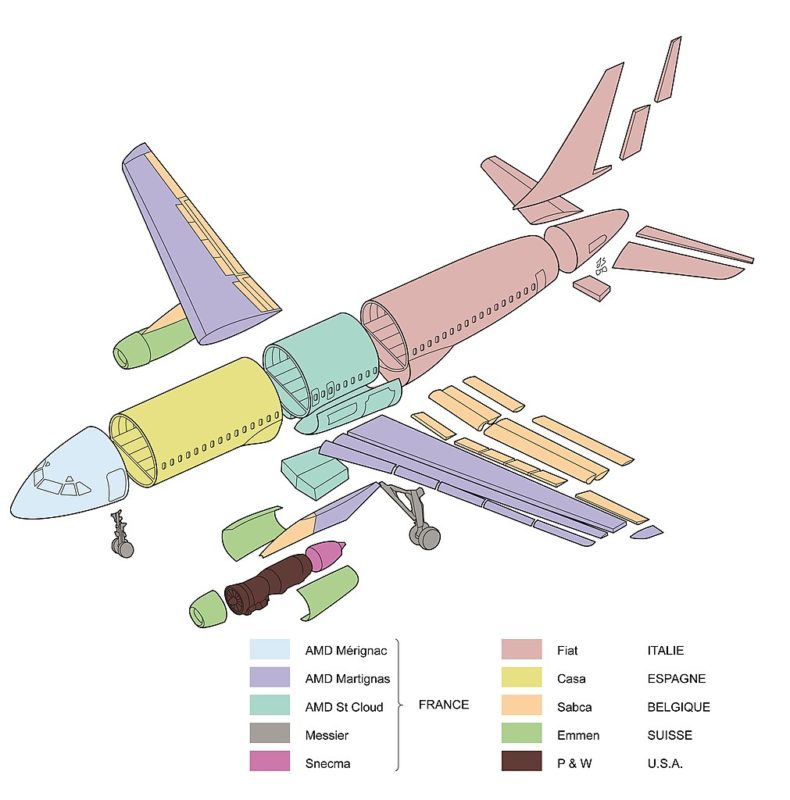

Total start-up costs were estimated at a billion French Francs (equal to €1.138 billion today), with 56% of the investment underwritten by the French government, 14% by Dassault itself, and the remaining 30% by a European consortium of subcontractors looking a bit like an embryonic Airbus consortium – Fiat of Italy signed on to build the vertical stabiliser and rear fuselage, CASA of Spain the rest of the fuselage, SABCA of Belgium ailerons and spoilers, FW Emmen of Switzerland the engine nacelles, and Canadair across the Atlantic in Montreal contributed the engine pylons.

Three factories in France were designated to make components to keep up with planned production of five aircraft per month – Poitiers, Martignas (near Bordeaux) and Seclin (near Lille). Final assembly was to take place at Istres. Break-even was estimated at 200 airframes, and 300 by the end of 1979 was the goal. French domestic carrier Air Inter ordered ten aircraft and the programme was officially underway, with construction beginning on two prototypes at Dassault HQ at Bordeaux-Merignac.

However, despite the new airliner’s excellent pedigree and its manufacturer’s high hopes, storm clouds were already brewing on the horizon. The biggest difference between the Mercure and the Boeing 737-200 was range. While even the earliest incarnation of the baby Boeing could fly for 4,800 kilometres (2,992 miles),

the Mercure was so carefully tailored to the needs of domestic-only Air Inter that it was crippled by a maximum range of only 2,000 kilometres (1,295 miles), and, with maximum payload, only 1,000 kilometres (621 miles).

Admittedly, Europe is a small continent, and a radius of 1,500 kilometres (932 miles) around Frankfurt includes Madrid, Tallinn, Palermo and Shannon. But plenty of city pairs considered ‘short haul’ far exceed that, such as London to Athens (2,400 kilometres / 1,500 miles), Toronto to Miami (1,984 kilometres / 1,233 miles) or Sydney to Auckland (2,165 kilometres / 1,345 miles). Add in the lack of fuel available at some ports resulting in the need to tanker fuel for the flight home, and the Mercure simply wasn’t able to offer the flexibility airlines needed.

It was joked that the lack of orders was a result of the aircraft itself not having the range to leave France – and no doubt, this lack of compatibility with the rest of the world’s airlines was the major obstacle to success. Additional factors were the 1973 oil crisis which raised operating costs and made airlines risk-averse. Devaluation of the US dollar made the export price of the Mercure unattractive, as well as the lack of global product support infrastructure that was offered by Boeing and Douglas.

Even Air France, who were already planning ahead for a Caravelle replacement, balked at the Mercure. Plenty of other airlines were curious, most notably Belgian flag carrier Sabena, but in the end not a single other order materialised. Despite the tumbleweed rolling through the sales suite, it was decided to go ahead with producing Air Inter’s order under a complex agreement between the airline, Dassault, and the French government to defray the high cost of producing small runs of spare parts to sustain the operation of just ten aircraft.

The irony was, lack of range aside, the Mercure was a fabulous aircraft. Its military pedigree gave it fighter-jet performance; on Air Inter’s shortest routes (known as Type A ‘minimum time’ trips), the profile was a high speed climb all the way up to 35,000 feet for a short cruise just a fraction under Mach 0.85 (380 knots equivalent airspeed) followed by a descent still at 380 knots all the way down, with 50% airbrakes extended at 6,000 feet and full airbrakes at 4,000 feet.

Only at 1,100 feet and eight kilometres (5 miles) out was the speed reduced back to 210 knots, airbrakes retracted and flaps extended first to 3 degrees, then 12 and finally 25 degrees and gear down for landing.

In fact with throttles closed and full airbrakes, the Mercure could descend at 14,000 feet per minute – two minutes from cruise to the ground.

In the 1980s, to manage increased traffic in terminal areas, France adopted the worldwide speed limit of 250 knots below 10,000 feet, and increased fuel costs resulted in slower cruise speeds; therefore some speed records between French city pairs set by Mercures will never be broken.

The Mercure was the first airliner to have a Head Up Display (HUD) for pilots, which allowed take-offs with forward visibility (RVR – Runway Visual Range) as low as 100 metres (328 feet).

Following on from the pioneering all-weather automatic landing systems developed by Air Inter for the Caravelle, the Mercure was capable of landing in Cat IIIa conditions, with a decision height eventually as low as 35 feet and an RVR of 125 metres (410 feet). The cockpit was fitted with two instruments that remain unique among civil transports: an Angle Of Attack (AOA) indicator used to illustrate lift generated by the wing, which allowed pilots to fly visual approach speeds accurate to within a single knot, and a G meter to avoid exceeding airframe structural limits (which were +2.5G and -1G).

The passenger cabin offered a spacious six-abreast configuration with enclosed overhead bins from day one, and innovative polarising windows instead of sliding window shades which passengers could lighten or darken by rotating a small button at the base of the window, just like on the Boeing 787 Dreamliner of today (albeit, due to high maintenance costs, the buttons were soon immobilised and windows left in the lightest position).

Mercure 01 F-WTCC was rolled out on April 4, 1971 and took to the air for the first time on May 28. The first production aircraft, designated as a Mercure 100A, followed on September 7 of the following year. The first true production aircraft intended for delivery to Air Inter first flew on July 19, 1973. Test flying took place mostly in France, with hot weather trials in Casablanca. Although the aircraft and its systems performed flawlessly in the test programme, a defect in the metallurgy of the upper wing surfaces resulted in discoloration known as “leopard spots” and this set the programme back by six months; certification by France’s DGAC regulatory body was granted on February 12, 1974, and the first ship was delivered to Air Inter on May 16. The production variant was dubbed the Mercure 100.

Trial passenger service began ad hoc from Air Inter’s base at Paris Orly on June 4, with service to Lyons, Bordeaux and Toulouse; the first ‘official’ service took place on June 14 from Paris to Marseilles. The type appeared in the timetable for the first time in the winter 1974/1975 edition, with the abbreviation DAM being used to designate the type. Air Inter did virtually no international flying but Mercures were occasionally seen at London Gatwick, Shannon, Dublin, Ibiza, Malaga, Madrid and Palma on charter flights for sports teams or package tour operators transporting French holidaymakers to beaches. Air France wet-leased Mercures on a few occasions, notably in the late 1970s to fly schedules from Nice to Geneva.

Following the abject commercial failure of the Mercure 100, at the beginning of 1973 Dassault proposed the Mercure 200C, with seating for 140 passengers and a range of 2,200 kilometres (1,400 miles) in co-operation with Air France. The French government promised a loan of 200 million French Francs (slightly over €200 million in today’s money) to create the new variant, but Air France insisted on the uprated JT8D-117 engine instead of the basic JT8D-15. Accommodating the larger engine would cost an additional 80 million Francs, at which point the government, fed up with the troubled programme, insisted that Dassault pay half the cost of the new development. Weighed down by the failure of the Mercure 100, Dassault had no choice but to cancel the project.

A CFM International CFM56-powered Mercure 200 (no C suffix this time) was proposed in 1975 as a machine that could be built under licence in the United States by Lockheed or Douglas. Concerns in France that the CFM56 would not be built slowed down negotiations, which then ended when Douglas stretched the DC-9 to create the DC-9-50.

The Mercure’s future didn’t quite end there. Air Inter actually added an eleventh Mercure to their fleet in the early 1980s; given the aircraft’s notoriously poor sales history this was greeted with faux (or perhaps genuine) amazement by the world’s aviation press (Flight International, usually sober and business-like for the most part, ran the story at the top of the first page of news for the week, with exclamation mark: “Air Inter Orders Another Mercure!”). The aircraft in question was the second prototype, F-WTMD, refurbished to 100 standard, reregistered F-BTMD and delivered to the airline on September 15, 1983.

Air Inter pilots, many of whom had a military background, fell in love with the Mercure. (Nervous passengers, it must be said, were less excited by the aircraft’s capacity for high G acceleration and precipitous descents.) The aircraft was intended to be operated by a two-person crew, but pressure from pilots unions resulted in the addition of a flight engineer. The Mercure did not have a specific panel for the officier mecanicien navigant, but the role was a busy one, including the exterior pre-flight inspection (performed anti-clockwise, contrary to usual practice elsewhere in the world), cockpit preparation, reading of checklists, setting thrust levers for takeoff, climb and cruise, systems monitoring, and a third pair of eyes to oversee the operation and spot traffic.

The Mercure enjoyed a perfect safety record in its flying career. The only serious incident occurred to F-BTTJ on August 17, 1986 (the author’s fourteenth birthday) en route from Paris to Grenoble as IT623. The flight encountered a severe hailstorm, hammering the forward windscreens until they were completely opaque. Captain Roger Franchet diverted to Lyons and landed the plane by donning a set of smoke goggles, opened his side window and sticking his head out to see forward. No passengers were injured – although a flight attendant chipped a tooth on the PA microphone during the heavy turbulence in the eye of the storm.

Wrapping up a 21 year working career, the last Mercure flights operated on April 29, 1995, after 360,815 hours carrying 44 million passengers on 430,916 flights – with 20,704 Cat IIIa autolands, 1,437 of them in actual low visibility Cat IIIa conditions. Average sectors flown per day per aircraft was eight, with an average flight time of 50 minutes.

As an aside, much of the technology as well as the concept of pan-European outsourcing created a template that led to the Airbus product line which today leads the world in producing civil airliners. The failure of the Mercure also contributed to the success of Airbus by demonstrating the need to create a platform that is flexible enough to cater to a wide range of different customer requirements. An expensive lesson, perhaps, but the versatility of the A320 is one of its greatest attributes, and didn’t come out of nowhere.

Seven Mercures are preserved to this day, six in France and one at the Technik Museum at Speyer in Germany, the highest percentage of any subsonic airliner of all time, reflecting its important role in aviation history and its popularity with the French public and aviation establishment.

Cover Image: Wikimedia Commons/Eduard Marmet