On February 24, 1989, a United Airlines Boeing 747 was operating flight UA811 from Los Angeles to Sydney with stops in Honolulu and Auckland. However, while climbing out of Honolulu bound for Auckland, a loud explosion was heard, and the cargo door on the right side of the plane suddenly blew away, creating a large hole in the side of the aircraft.

In addition, the resulting explosive decompression blew out several rows of seats, killing nine passengers whose bodies were never found. Despite all the hurdles, the crew miraculously landed Flight UA811 without any further incidents and saved the lives of the remaining 346 people on board.

Flight Details

The Boeing 747-100 with registration N4713U was operating flight UA811 from Los Angeles to Sydney with 3 flight crew, 15 flight attendants and 337 passengers aboard. The aircraft was the 89th 747 that was manufactured and it had completed a total of 58,814 flight hours at the time of the incident.

Flight UA811 was under the command of Captain David Cronin who had around 28,000 total flight hours, including 1,600 flight hours in the Boeing 747. The 59-year-old captain was accompanied by First Officer Gregory Allen Slader, who had 14,500 total flight hours. Also, onboard the flight was Flight Engineer Randal Thomas, who had 20,000 total flight hours. Flight 811 was Captain Cronin’s penultimate scheduled flight before his mandatory retirement.

At 1:52 Honolulu Standard Time (HST), Flight 811 departed from Honolulu International Airport. The captain was at the controls when the flight was cleared for takeoff from runway 08R. During the climb, the crew noticed thunderstorms both visually and on the aircraft’s weather radar. As a result, they requested and were granted clearance for a course deviation to the left from the Honolulu Combined Center Radar Approach Control (CERAP). The captain made the decision to keep the passenger seat belt sign turned on.

However, while the aircraft was climbing between 22,000 and 23,000 feet, a loud explosion was heard, and the cargo door on the right side of the plane suddenly blew open, creating a large hole in the side of the aircraft.

As a result of the sudden decompression, a rush of air sucked out nine passengers, along with much of the interior of the affected portion, including seats, luggage, and debris. The cockpit crew donned their respective oxygen masks but found no oxygen available. The aircraft’s cabin altitude horn sounded and the flight crew believed the passenger oxygen masks had deployed automatically.

Emergency Descent and Turn Around

The captain took immediate action by initiating an emergency descent, making a 180-degree turn to the left to avoid a thunderstorm, and heading towards Honolulu. Meanwhile, the first officer informed CERAP that the aircraft was in an emergency descent and seemed to have lost power in the No. 3 engine.

At around 02:20 HST, the appropriate 7700 emergency code was placed in the aircraft’s radar beacon transponder, and an emergency was declared with CERAP. Shortly after the descent began, the No. 3 engine was shut down due to heavy vibration, no N1 compressor indication, low exhaust gas temperature (EGT), and low engine pressure ratio (EPR).

The second officer left the cockpit to inspect the cabin area and found that a large portion of the forward right side of the cabin fuselage was missing. After returning to the cockpit to report this to the captain, the No. 4 engine was also shut down due to high EGT and no N1 compressor indication, which were accompanied by visible flashes of fire. The flight crew also initiated fuel dumping during the descent to reduce the aircraft’s landing weight.

Flight UA811 was cleared for an approach to Honolulu runway 8L. During the final approach, the flight crew used only the No. 1 and No. 2 engines, flying at a speed of 190 to 200 knots. As they extended the flaps, they noticed asymmetrical flap indication as the flap position approached 50. The crew then decided to extend the inboard trailing edge flaps to 100 for landing.

However, the right outboard leading edge flaps did not extend during the flap lowering sequence. The aircraft touched down on the runway about 1,000 feet from the approach end and eventually came to a stop about 7,000 feet later. The captain applied idle reverse on the No. 1 and No. 2 engines and used moderate to heavy braking to stop the aircraft.

Evacuation, Fatality and Injuries

At 02:34 HST, the flight crew notified the Honolulu tower that the aircraft was stopped and an emergency evacuation had commenced on the runway.

No remains of the nine passengers lost during the flight were discovered despite extensive air and sea searches. However, various small body fragments and articles of clothing were recovered from the Number 3 engine, indicating that at least one victim was sucked out of the fuselage and ingested by the engine. It was unclear whether the fragments belonged to single or multiple victims.

The evacuation of all remaining passengers and flight attendants from the aircraft was completed in under 45 seconds. However, every flight attendant incurred some form of injury during the evacuation, ranging from minor scratches to a dislocated shoulder. One of the cockpit crew and 20 passengers sustained minor injuries whereas two passengers were seriously injured.

“There was grey swirling smoke and debris flying everywhere. As I was being thrown down, I watched ceiling panels fall; door panels and side panels blew off. Big panels fell on people’s heads. It was like an implosion. Everything came down from the ceiling and the walls inward to us.”

Curtis, flight attendant, United Airlines flight 811

Aircraft Damage

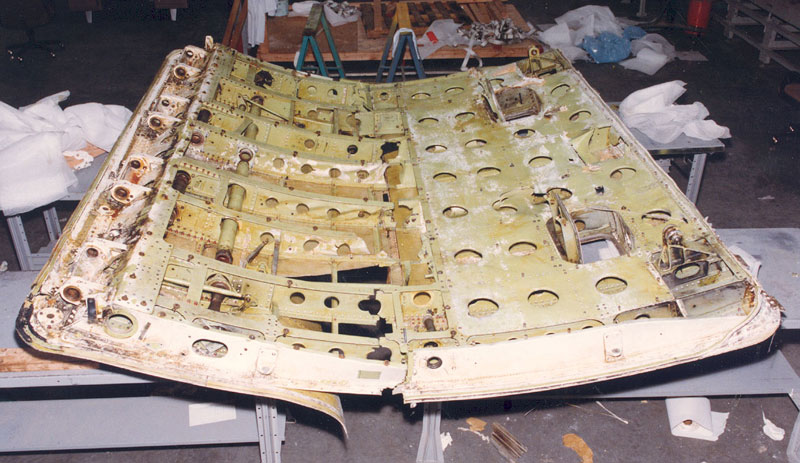

The most significant damage to the aircraft was concentrated on the right side, specifically in the forward lower lobe cargo door area, where a hole approximately 10 by 15 feet in size had appeared. The cargo door fuselage cutout lower sill and side frames remained intact, but the door was missing.

An area of the fuselage, measuring about 13 feet in length and 15 feet vertically, had separated from the aircraft above the cargo door, extending to the upper deck windows. The floor beams situated adjacent to and inboard of the cargo door area had buckled and fractured downward.

Moreover, portions of the right-wing, right horizontal stabilizer, vertical stabilizer, and engines No. 3 and No. 4 were damaged by debris. Engines No. 1 and No. 2, as well as the left side of the aircraft, did not appear to have been damaged. Specifically, the right wing had incurred impact damage along the leading edge between the No. 3 engine pylon and the No. 17 variable camber leading edge flap, with slight impact damage noted on the No. 18 leading edge flap.

The aircraft also sustained extensive damage to the right wing and various parts of the fuselage. There were scuffs, dents, and punctures in multiple locations, including the wing leading edge, Krueger flaps, and flap track canoe fairings. Cargo door separation caused significant damage to the fuselage and cabin floor structure. The cabin pressurization out-flow valves were found fully open, and the majority of the cabin floor-to-cargo compartment blowout panels were activated.

Based on the repair costs estimated by United Airlines, the aircraft incurred damage of $14,000,000 at that time.

Investigation and Findings

The investigation into the United Flight 811 incident was conducted by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) in collaboration with other aviation safety organizations.

A comprehensive search of the ocean, both on air and water, was carried out right after the incident, but it was unsuccessful in locating the sections of the aircraft that were lost due to the explosive decompression. Two sections of the cargo door of Flight 811 were retrieved from a depth of 14,100 feet (4,300 m) in the Pacific Ocean on September 26 and October 1, 1990. As a result, the NTSB reopened and completed the investigation.

Although a number of contributing factors were identified, the NTSB has concluded that the likely reason for this incident was the sudden opening of the lower lobe cargo door in mid-air and the consequent explosive decompression.

- The malfunctioning of a switch or wiring in the door control system allowed electrical activation of the door latches, causing them to move towards the unlatched position after the initial closure and before takeoff.

- The design of the cargo door locking mechanisms was deficient, which resulted in their deformation, making the door unlatch even after it was properly latched and locked.

- Additionally, Boeing and the FAA did not take prompt corrective measures following a cargo door opening event on a Pan Am B-747 in 1987, which also contributed to the accident.

Aftermath

Following the investigation of UA811, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) issued several safety recommendations to improve flight safety. These recommendations were aimed at Boeing, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), and United Airlines. The NTSB recommended Boeing improve the design of its cargo door locking mechanisms to prevent deformation, which could lead to an unlatched door. They also recommended the FAA strengthen its oversight of aircraft manufacturers and ensure that corrective actions are taken promptly.

United Airlines took several steps to improve safety following the accident. They implemented a new cargo door warning system on their 747 aircraft, which alerts the flight crew if the cargo door is not properly secured before takeoff. Additionally, they established a new maintenance program for cargo doors, including more frequent inspections and repairs.

Moreover, the crew of Flight UA811 was praised for their quick thinking and professionalism, which undoubtedly saved many lives. The passengers who lost their lives in the incident were remembered and honoured, and their families were provided with support and assistance.

Feature Image via stuff.co.nz

I didn’t see anything about the oxygen situation. Why didn’t the cockpit crew get any O2 when they put on masks? Was that part of the damage, or was there a previous maintenance issue? I thought it was mandatory for one pilot to be on oxygen “just in case.” No so?

I happened to be on flight 811 on 24 February 1989 traveling to Australia.

Oh my God, what a nightmare.

We just heard a bang , something like the sound of a bomb .

Next moment debris was flying all over the aircraft, some passengers were laughing loudly, others praying and the majority 😢 histerically.

Captain made several announcements and none of us could hear anything .

May all of those first class passengers that were sucked out of the aircraft rest in peace 😢

Thank you United Airlines for your assistance after the disaster.

Wow I can’t imagine going through something like that God was watching you all that night

Hi. I think there is a correlation to electrical transients. Uncommanded door openings are not unusual. Some airframes operating manuals require the door actuator circuit breakers must be pulled for flight. See DC8 incidents.

The mechanism may be a common failure mode of the 400-HZ line contractors used to power the A/C units. If one set of contacts fail to open, the A/C pack will single-phase. As the units of the early 747s draw over 100 kVA, This can cause a severe voltage transient on the mains. The door command generally uses negative logic, the signal is considered when voltage goes low. In tropic airports, with high humidity, the A/C units are working hard. But a the aircraft climbs out, the outside air temp drops rapidly. Voltage transients are always caused by circuits opening, not closing in.