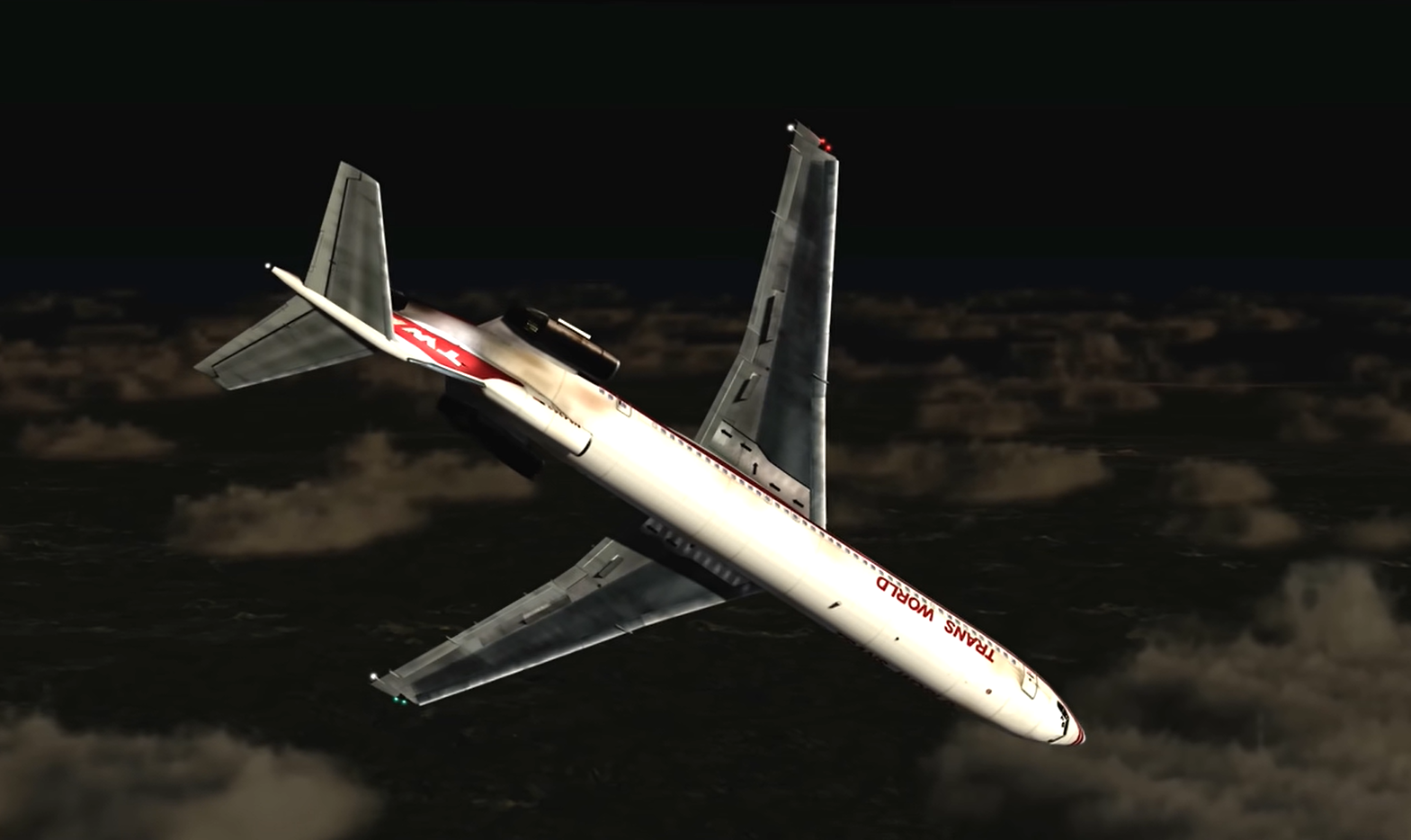

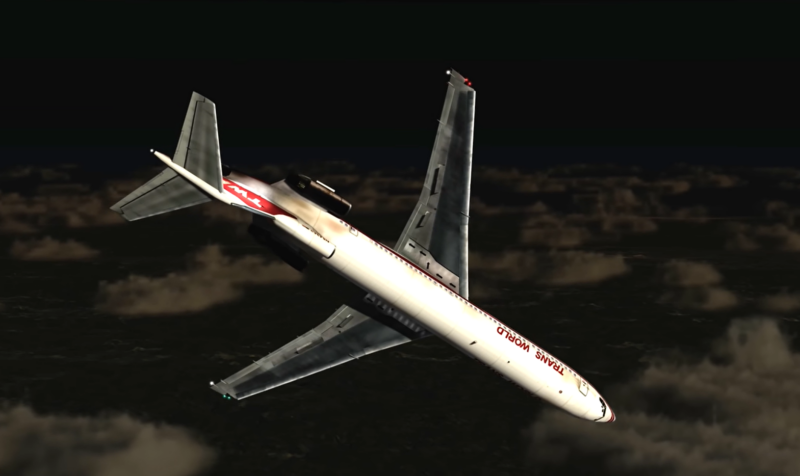

On April 4th, 1979, a TWA flight bound for Minneapolis experienced a sudden and terrifying roll in the air, losing more than 30,000 feet in a matter of seconds. As the aircraft plunged while cruising at 39,000 feet, it completed two full 360-degree rolls and surpassed the maximum allowable airspeed for the Boeing 727 aircraft.

Thankfully, the crew gained control of the aircraft at about 8,000 feet and safely landed at Detroit Metropolitan Airport.

Flight Details

The Trans World Airlines Boeing 727-31 with registration N840TW was performing flight TW841 from New York’s JFK Airport to Minneapolis-Saint Paul International Airport in Minneapolis. The flight was under the command of Captain Harvey G. “Hoot” Gibson who had over 15,700 total flight hours in his log. Captain Gibson was accompanied by First Officer Jess Scott Kennedy who had completed over 10,300 flight hours and Flight Engineer (Second Officer) Gary N. Banks who had 4,186 hours of flight time.

After a delay of about 45 minutes due to traffic congestion, Flight 841 departed JFK with 82 passengers and 7 crew members aboard at 20:25 EST. About thirty minutes into the flight, it reached FL350, to which it had been cleared. At 21:24, the flight called Toronto Center and asked for any report on winds at FL310 or FL390. The Toronto Center controller replied that he had no reports from other flights.

Flight 841 stated that it was encountering a headwind of 100 knots or more, and shortly after, the pilots requested clearance to FL390.

Subsequently, the flight was cleared to FL390, and the captain initiated a climb at 0.80 mach, levelled the aircraft at 39,000 feet at that speed, and engaged the autopilot in the Altitude Hold mode. The takeoff, climb, and en route portions of the flight were uneventful and no problems were found until about 9 minutes after the aircraft reached FL390.

TWA Flight 841 was cruising in visual flight conditions at FL390 with all systems indicating normal operation. The captain had the aircraft on autopilot in Altitude-Hold mode while he sorted maps and charts from his flight bag on the left cockpit floor. While he was sorting maps or charts, he felt a buzzing sensation. Within 2 or 3 seconds, the buzzing became a light buffet, and he looked at the flight instruments.

The captain noticed that the autopilot was commanding a turn to the left with the control wheel displaced accordingly, although the attitude director indicator (ADI) showed the aircraft in a 20° to 30° bank to the right. The ADI showed that the aircraft was continuing to bank to the right at a slightly faster-than-normal rate of roll, so he disconnected the autopilot and applied more left aileron control to stop the roll.

360° Roll

However, the aircraft continued to roll to the right, in spite of nearly full left aileron control, so he also applied left rudder control. Despite these inputs, the roll continued and the captain realized that the aircraft was going to roll inverted. He then retarded the throttles to the flight idle position, and stated “We’re Going Over.” While still cruising at FL390, the aircraft suddenly initiated a steep and uncontrolled roll to the right, which led the aircraft to enter a spiral dive. The aircraft rolled completely and entered a second roll with the nose down.

After the aircraft entered an uncontrolled dive, the captain asked the first officer to extend the speed brakes. However, the F/O was busy calculating the aircraft’s groundspeed and was unaware of the buffeting or the aircraft’s attitude, so he didn’t understand the captain’s command. Captain Gibson then extended the speed brakes himself, but the aircraft continued to descend rapidly.

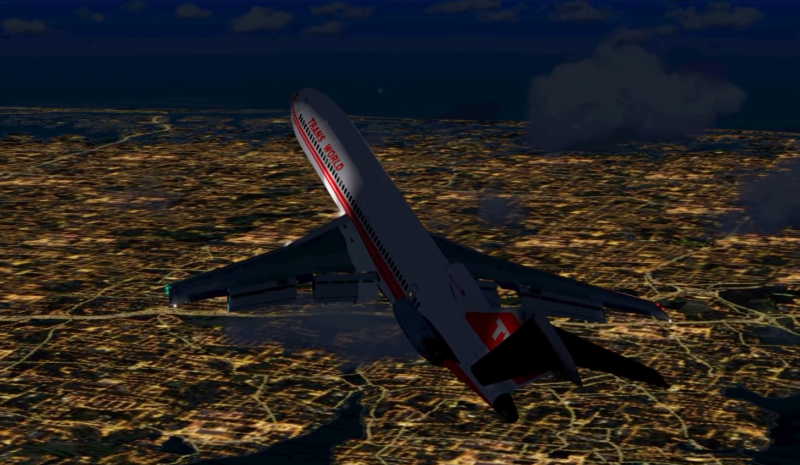

However, after receiving no response from the speed brake extension, the captain moved the control handle to the retract position and back to the extended position. The captain noticed that the airspeed needle was rapidly approaching its limit, and he could only see “black” on the ADI and bright areas in the windshield, which he thought were lights from towns shining through the undercast.

The altimeter was indicating a rapid descent that was difficult to read, but the aircraft was approximately at 15,000 feet, descending quickly when the captain ordered the extension of the landing gear. The first officer quickly moved the gear handle to the “extend” position, and a loud explosion-like sound was heard.

Throughout the descent, the captain applied a full left aileron and a full left rudder, but the aircraft continued to roll to the right. When the landing gear was extended, the captain relaxed some of the back pressure on the control column and the pressure on the aileron and rudder controls. As a result, the airspeed also began to slow down. He was able to roll the aircraft to a near wings-level attitude and stop the descent, and the aircraft pitched upward into a 30° to 50° climb.

The captain used the moon in the windscreen as a visual reference to manoeuvre the aircraft, and with guidance from the first and second officers, he levelled the aircraft near 13,000 feet.

During the incident, Flight 841 rapidly descended approximately 34,000 feet (10,000 m) in a mere 63 seconds. The incident occurred at night, at around 21:48.

Hydraulic Failure and Approach to Detroit

After regaining control of the aircraft, the pilots noticed a warning light indicating the failure of the ‘A’ hydraulic system and a warning flag indicating that the lower yaw damper was inoperative. After reviewing the situation, the captain decided to land the aircraft at Detroit Metropolitan Airport and instructed the F/O and flight engineer to perform emergency checklist procedures and to notify the flight attendants to prepare the passengers for an emergency landing.

The captain attempted to extend the landing flaps during the approach, but the aircraft rolled sharply to the left. Therefore, Captain Gibson ordered the flaps retracted and planned for a landing without flaps.

The two main landing gear indicators showed unsafe landing gear conditions, so the captain made a low-altitude pass down the runway for a check of the landing gear. The control tower and crash rescue personnel reported that all three landing gears appeared to be extended. At about 22:31, the captain landed the aircraft on Detroit’s runway 3 without incident.

Aircraft Damage and Injuries

During the violent roll and descent, the aircraft experienced high G-forces, which put stress on the structure of the plane. The rolling motion also caused objects within the cabin to become airborne, striking passengers and crew members. The cockpit voice recorder captured the sounds of screams, crashing objects, and the pilots struggling to regain control of the plane.

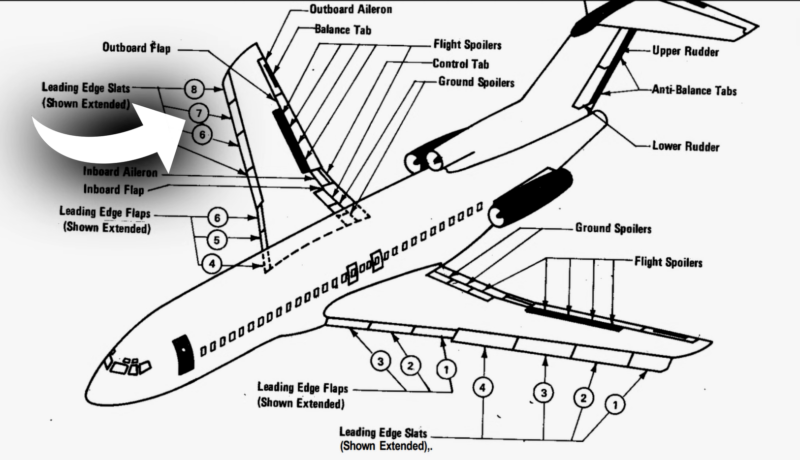

The No. 7 leading edge slat on the right wing was missing. The slat actuator cylinder was broken about 1 1/2 inches forward of its trunnion; the aft portion of the cylinder remained attached to the wing. Both main gear landing doors and their operating mechanisms were damaged extensively and a hydraulic line was ruptured. The nose gear door was also damaged.

Even though the flight crew members weren’t medically examined, five passengers reported injuries soon after landing in Detroit. Three of them were taken to a hospital for treatment of strains and bruises.

One passenger had a bruised and bleeding knee and a swollen ankle. Later, three more passengers reported injuries, but only one was hospitalized for severe muscle strain and vertigo/balance problems.

Investigation and Finding

Following the harrowing incident of TWA Flight 841, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) launched an investigation which was the lengthiest accident investigation in its history at that time.

The safety board determined that the incident was caused by the No. 7 leading edge slat remaining extended due to a pre-existing misalignment, combined with the flight crew’s manipulation of the flap/slat controls and the captain’s untimely flight control inputs. Analysis of the evidence found that the uncontrolled manoeuvre began when the No. 7 leading edge slat on the right wing of the aircraft became isolated in the extended or partially extended position, causing a slow roll to the right of about 35 degrees.

However, the Air Line Pilots Association (ALPA) disagreed with the NTSB findings and claimed a complex interaction involving lateral and directional flight controls on the B727 aircraft caused the accident. The crew members denied that their actions had been the cause of the flaps’ extension. On the contrary, the manufacturer stated that it was impossible for the flaps to extend without manipulating the controls.

According to the NTSB investigation, the roll was briefly stopped, but then resumed, with the aircraft rolling to about 35 degrees of right bank in approximately four seconds. At this point, the combination of Mach number, angle of attack, and sideslip reduced the aircraft’s lateral control margin to zero or less, and the aircraft continued to roll to the right in a descending spiral. Over the next 33 seconds, the aircraft completed a 360-degree roll while descending to about 21,000 feet. During this time, the No. 7 slat was torn from the aircraft. Control of the aircraft was regained at an altitude of about 8,000 feet.

Gibson and the ALPA appealed the NTSB’s findings multiple times from 1983 to 1995. They appealed to the NTSB and the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, but both appeals were dismissed. The NTSB rejected their petition for lack of new evidence, and the court dismissed the appeal for lack of jurisdiction since the NTSB’s decisions are not subject to review.

Following the investigation, the aircraft was repaired and returned to service in late May 1979.

Feature Image: TheFlightChannel