On October 28, 2016, American Airlines Flight 383 experienced an engine failure during its takeoff roll at Chicago O’Hare. The uncontained failure of the right engine led to a severe fire, the B767 was declared a total hull loss.

Flight Details

The Boeing 767-300 with registration N345AN was performing flight AA383 from Chicago O’Hare to Miami with 161 passengers and 9 crew members onboard. The flight was under the command of a 61-year-old captain Anthony Kochenash who had approximately 17,400 flight hours, including 4,000 on the B767. He was accompanied by a 57-year-old first officer David Ditzel who had about 22,000 flight hours, including 1,600 on type.

At 14:30 (2:30 PM) Central Daylight Time (CDT), the tower controller cleared flight AA383 for takeoff on Chicago’s runway 28R. The F/O acknowledged the instruction and the aircraft commenced its takeoff roll one minute later with Captain Kochenash as the pilot flying (PF) and First Officer Ditzel as the pilot monitoring (PM).

Shortly after commencing the takeoff roll, at 14:31:32, F/O Ditzel called out “eighty knots,” however, 11 seconds after this callout was made, the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) recorded a loud noise. Soon after at 14:31:43.4, with the airplane’s airspeed indicating 128 knots, the longitudinal acceleration decreased suddenly from 0.23 to 0.13 G. Simultaneously, variations in the vertical acceleration increased in magnitude, consistent with a sudden engine imbalance causing a vibration force on the airframe.

As a result, the aircraft began to veer right, and Kochenash rejected the takeoff. At that time, the aircraft’s airspeed was 134 knots, which was also the calculated takeoff decision speed (V1).

“American three eighty-three heavy stopping on the runway,” the F/O radioed to the control tower.

Having already noticed the engine failure, the controller responded with “Roger Roger. Fire,” informing the crew of the situation.

F/O Ditzel inquired, “Do you see any smoke or fire?” to which the controller replied, “Yeah, fire off the right wing.” The controller then promptly ordered the dispatch of fire trucks to the aircraft.

Evacuation

In the meantime, Captain Kochenash initiated the engine fire checklist; the right engine was shut off, and its fire extinguisher was activated. Subsequently, Kochenash called for the evacuation checklist.

While performing the checklist, the captain heard “commotion” outside the cockpit door and realized that the flight attendants had already initiated an evacuation. Following the fourth step in the checklist – shutting down the left engine, the captain announced an evacuation to the cabin and activated the emergency evacuation signal switch.

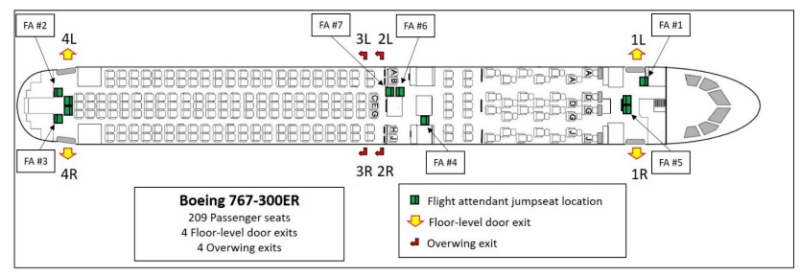

The first emergency exit (the left overwing window exit) was opened 8 to 12 seconds after the aircraft stopped, followed approximately 17 seconds later by the forward left door and then approximately 4 seconds later by the forward right door. After finalizing all the remaining steps of the evacuation checklist, the captain exited the cockpit. While exiting the aircraft, both flight crew members observed “a lot of smoke” in the cabin.

Injuries and Aircraft Damage

During the evacuation, one of the passengers sustained a serious injury, and one flight attendant along with 19 passengers suffered minor injuries. The 20 injured passengers were transported to local hospitals to receive treatment, and all were released within 24 hours.

Footage taken during the evacuation and postaccident interviews with flight attendants highlighted that some passengers evacuated from all three usable exits with carry-on baggage. In one case, a flight attendant tried to take a bag away from a passenger who did not follow the instruction to evacuate without baggage, but the flight attendant realized that the struggle over the bag was prolonging the evacuation and allowed the passenger to take the bag.

In another case, a passenger came to the left overwing exit with a bag and evacuated with it despite being instructed to leave the bag behind. Passengers evacuating the aircraft with carry-on baggage has been a recurring concern and the NTSB raised this concern in its investigation report.

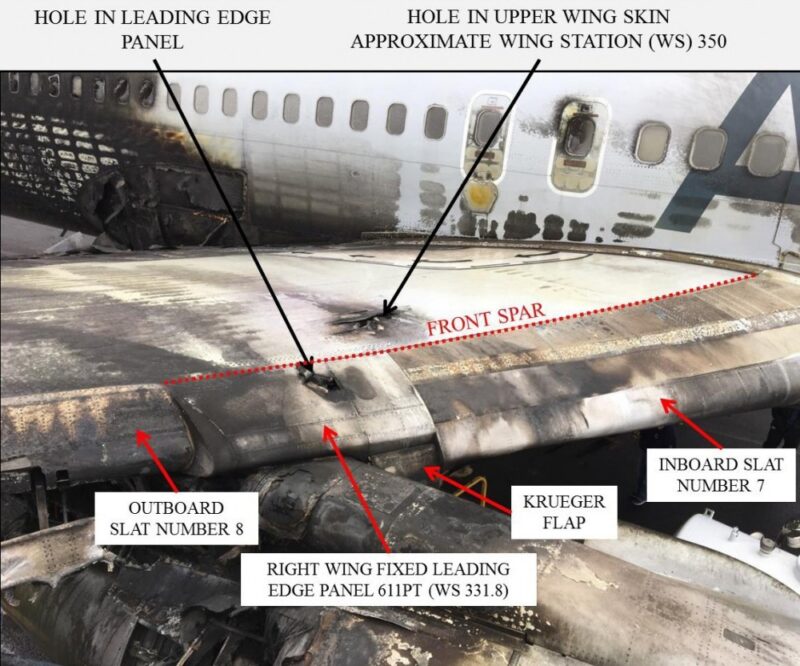

The predominant fire damage was confined to the right engine, right-wing, sections of the right fuselage, and the right horizontal stabilizer.

The aircraft came to its final stop on runway 28R, approximately 5,975 feet from the N5 intersection, the point of origin for the takeoff roll, leaving about 3,775 feet of runway ahead. Marks from the left and right main landing gear tires, indicative of braking, were observed on the runway surface starting around 3,961 feet from the N5 intersection. These braking marks persisted for about 2,284 feet, concluding at the aircraft’s final position on the runway.

Extensive fire damage affected the right side of the fuselage, leading to the collapse of the right-wing approximately midway along its length. Consequently, American Airlines designated the aircraft as a hull loss. This incident represents the 17th hull loss involving a Boeing 767.

Investigation

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) launched an investigation and its preliminary investigation results found that the right-hand engine’s stage 2 high-pressure turbine (HPT) disk fractured into at least 4 pieces. One of the fragments impacted the right engine, right-wing, and portions of the right fuselage, severing the main engine fuel feed line and breaching the right-wing fuel tank, which led to a fuel-fed fire.

As a result of the uncontained engine failure, a fuel leak resulted in a pool fire under the right wing. The NTSB concluded that the right engine experienced an uncontained HPT stage 2 disk rupture during the takeoff roll. The HPT stage 2 disk initially separated into two fragments.

One fragment penetrated through the inboard section of the right wing, severed the main engine fuel feed line, breached the fuel tank, travelled up and over the fuselage, and landed about 3,000 ft away. The other fragment exited outboard of the right engine, impacting the runway and fracturing into three pieces.

Probable Causes and Findings

The NTSB determined that the probable cause of this accident was the failure of the high-pressure turbine (HPT) stage 2 disk. This malfunction led to the severance of the main engine fuel feed line and a breach in the right main wing fuel tank, releasing fuel that resulted in a fire on the right side of the aircraft during the takeoff roll.

The HPT stage 2 disk failed because of multiple low-cycle fatigue cracks originating from an internal subsurface manufacturing anomaly, known as a discrete dirty white spot, that was most likely undetectable during both production and subsequent in-service inspections using the established procedures.

Contributing to the serious passenger injury was the delay in shutting down the left engine and a flight attendant’s deviation from company procedures, leading to passenger evacuation from the left overwing exit while the left engine was still operational. This delay was further influenced by the absence of a dedicated checklist procedure for Boeing 767 aircraft that specifically addressed engine fires on the ground and the lack of communication between the flight and cabin crews after the aircraft came to a stop.

The failed turbine disk was recovered in four pieces, one of which weighed 57 pounds and was found more than a half mile from the aircraft. Through extensive examination of the disk fragments at the NTSB lab, investigators determined there was a subsurface defect in the disk at the time of manufacture. Because of the nature of the defect and the limits of inspection methods, the NTSB concluded the defect was likely undetectable when the disk was produced in 1997.

Investigators further determined the defect had been propagating microscopic cracks in the disk for as many as 5,700 flight cycles, before the accident. Although the disk had been inspected in January 2011, the NTSB said the internal cracks were also most likely undetectable at that time because the required inspection methods at that time were unable to identify all subsurface defects.

Safety Recommendations

In light of the investigation findings, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) has issued key safety recommendations. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) was urged to lead an industry group assessing inspection technologies for nickel alloy engine components, mandating subsurface inspection techniques and revising Advisory Circulars for enhanced safety.

The NTSB also advised developing emergency checklist procedures for ground engine fires and emphasising effective exit assessment training for flight crews. Additionally, research was recommended on the effects of carry-on baggage during evacuations.

Boeing was also directed to collaborate with B767 operators in revising emergency checklists for ground engine fires. Furthermore, American Airlines was instructed to review engine fire checklists for all aircraft to ensure prompt handling of ground engine fires without compromising evacuation procedures.

In response to the investigation, GE Aviation issued a Service Bulletin recommending regular inspections of first- and second-stage disks of CF6 engines built before 2000. The FAA subsequently issued an airworthiness directive mandating ongoing ultrasonic inspections for cracks in stage 1 and stage 2 disks on engines like those involved in Flight 383.

Feature Image: OnDisasters