Cathay Pacific is one of the biggest and most important airlines in the world: number ten globally by sales revenue, number one in the world for cargo. Its base, Hong Kong, is number eight in the world for passengers and number one in the world for cargo. No plane symbolised Cathay’s march towards Europe, followed by their long and prestigious transpacific runs to Los Angeles, San Francisco and New York like the Boeing 747.

Cathay and the 747

Cathay Pacific was founded as the Roy Farrell Export-Import Co. in 1946 by a pair of ex-military pilots, Sydney de Kantzow (an Australian) and Roy Farrell (an American) to serve Hong Kong; the name Cathay Pacific was chosen later the same year during a late-night session at the Manila Hotel. (Incidentally, in Chinese the airline is aptly called “grand and peaceful state”.) Because of Hong Kong’s status as a British Dependent Territory from the mid 1800s until being handed back to China on July 1, 1997, it didn’t have statehood and therefore was unable to negotiate much in the way of long haul air treaties, and most of the flying from there was done by British Airways. In Cathay’s early days, it was only able to secure traffic rights to local ports such as Taipei, Bangkok, Singapore, Manila, Jakarta and down to Australia.

The fleet included Douglas DC-3 and Lockheed Electra propliners, followed by early jets such as the Convair CV-880A (a fleet of nine, mostly acquired from VIASA and Japan Airlines) and the Boeing 707 (a fleet of fifteen, mostly acquired from Northwest Orient). Cathay moved up a league in 1975 with the purchase of two widebody L-1011 Tristar widebodies from Lockheed, a love affair which resulted in the procurement of nineteen more secondhand examples, mostly from Eastern Airlines in the USA but also British Airways, Air Lanka, Court Line and Air Transat. These were L-1011-1s with limited range, and Cathay was still restricted to the local region.

The big breakthrough came in 1980 when Cathay finally secured traffic rights to serve London, and received its first Boeing 747-267B on July 20, 1979, Rolls-Royce engines not only pacifying its colonial masters in the United Kingdom but also for compatibility with the Tristar fleet. The registration displayed local pride: VR-HKG. After being inaugurated on the Sydney run in August and bringing extra capacity to local routes within Asia, the jumbo’s London Gatwick debut (via Bahrain) took place the following year, on July 16, 1980.

The fleet of 747-200s expanded to twenty-seven aircraft: fifteen people movers and twelve dedicated freighters. Cathay Pacific opened transpacific service to Vancouver in 1983 and to San Francisco in 1986. Half a dozen 747-367s joined the fleet starting in 1985, bringing extra capacity in the stretched upper deck, but incorporating the same cockpit, wing and engines as the -200 – a “minimum change” upgrade. A major evolution to the 747 was in the works, driven by customers including Cathay, and 1989 Boeing unveiled the 747-400 which went on to become the best-selling variant of the jumbo, arriving just in time for the post-Cold War peace dividend of the 1990s. Cathay Pacific bought eighteen passenger models and twelve freighters directly from Boeing and, in the 2000s, another seven ex-Singapore Airlines 747-412 Megatops despite having different Pratt & Whitney powerplants.

The 747 in Cathay’s jade green colours was a staple at airports across Asia and further afield as the airline took its place among the biggest travel brands in the world. In 1998, one of the 747-467s operated the inaugural flight into Hong Kong’s Chep Lap Kok airport which replaced the famous but undersized Kai Tak, with a fifteen-hour, thirty-five minute flight from New York’s JFK via the North Pole. By the mid-2000s Cathay jumbos were operating daily passenger service at cities as distant from Hong Kong as New York, Johannesburg, Frankfurt and Dubai, as well as multiple frequencies to strongholds such as London, Los Angeles and across Australia. Due to the volumes on local routes in the region, the 747s were mainstays on trips to Bangkok, Singapore, Beijing, cities in Japan, plus of course the “golden route” to Taipei.

However, the twin-engined 777-300ER can do pretty much anything the four-engined 747 can (but burning less fuel and needing half the maintenance), so when deliveries of Boeing’s twenty-first century miracle machine to Hong Kong began in late 2007, the writing was on the wall. By 2014 the passenger fleet of 747-400s at Cathay was down to half a dozen, and its last long haul destination was its first US destination: San Francisco, which ended on September 1. After that 747s were only used ad hoc to regional cities such as Taipei, Bangkok, Bali and Singapore when traffic demanded the extra capacity, with one just route still scheduled, the evening Hong Kong to Tokyo Haneda CX542, returning to base the following morning as CX543.

Cathay occupies a special place in the hearts of Australians, as Hong Kong is a major stopover for Aussies travelling to or from Europe – a place to spend a few days en route to get a suit or some shirts made, shop in the markets, stroll up Nathan Road, flag down a G&T at the Peninsula. Many Cathay pilots are Australian, some gravitating directly from flying school, others as refugees from the shutdown of Ansett Australia in 2001. Along with Singapore Airlines and Thai International, Cathay Pacific could be considered an Australian flag carrier, so important is the market to the airline’s bottom line, and so important is Cathay to mobilising generations of Australians.

One last flight

When Cathay announced the last flight of the 747 would take place on the Haneda route on October 1, 2016, this Australian couldn’t resist one last flight on a Cathay 747, and booked a ride using British Airways points on CX543 on September 27, 2016.

I stayed overnight at the Royal Park Hotel which is located right inside Haneda’s modern international terminal, so I needed to take no more than a few steps from the hotel reception area to Cathay’s check in desk. Although I was booked in Economy, I was able to use the First Class check-in thanks to my Emerald (top tier) status with fellow oneworld alliance member British Airways.

With nine First and forty-six Business seats on the jumbo, there was a line at the premium class check-in desks, but Cathay’s capable ground staff dealt with each customer swiftly and I was soon checked in by a friendly and helpful agent despite two legs on different bookings, and my two heavy bags were tagged through to Manchester, clearing the way for an uninterrupted nine hour stay in Cathay’s lounges at Hong Kong.

Cathay have laminated seat maps of the fleet at the check-in desk to show passengers where they’re sitting and what’s on offer (why every airline don’t do this is a mystery). I wanted to steal the 747 seat map but with three days left of 747 ops it might still be missed. I can only assume it’s now in the possession of a sticky-fingered enthusiast who was among the last to check-in on October 1. With help from the seat map, I picked a seat down the back in one of the outer pairs where 3-4-3 becomes 2-4-2.

After clearing security I used my BA gold status to spend an hour in the Cathay lounge on the top floor and commands an impressive view of airfield action. The approach to land involves a low-level bank to join finals very late, and every minute another jet, many of them widebody 777s and 787s on domestic runs, curved around to touch down outside the panoramic windows. A choice of Chinese or Japanese breakfast was offered, cooked to order and signalled when ready with a radio-controlled buzzer. I was pleased to see our 747 wasn’t the only one of its kind on the move, as a Thai jumbo landed from Bangkok. There is plenty of life in the old girl yet – on top of thirty-seven 747-8i at Koreanair, Air China and Lufthansa, AeroTransport Databank lists 185 active 747-400 passenger aircraft (British Airways, China Airlines, KLM, Qantas, Lufthansa and Thai all remain committed to the type at the time of writing).

I wandered down to gate 145 where a familiar sight awaited. The jade-green jumbo sat nose-in to the loading area, two jetbridges attached, cockpit and upper deck presiding over the surroundings. Passengers took pictures from the glassed-in boarding area — all Hong Kong locals, one of the most mobile populations in the world, have a love affair with the 747, and Japan too, since JAL and All Nippon at their peak operated more than two hundred machines including dozens dedicated to domestic runs, the biggest national fleet of jumbos in the world.

At this point, the very end of Cathay’s 747 operations, the fleet was down to three machines – B-HUI, -HUJ and HKT. The first two were delivered new to Cathay as 747-467s, and the latter an ex-Singapore Airlines -412. From spying the registration painted on the nosegear, today’s CX543 was to be operated by B-HKT, distinctive also for the Pratt & Whitneys under the wing, as opposed to Cathay’s original Rolls-Royce powered fleet.

Nonetheless, there was no sign of a previous owner. Boarding the aircraft definitely induced a grand and peaceful state, the soft green tones reinforcing the Cathay corporate brand which stands for reliability and luxury. With retirement of the fleet in the works for some time, the 747s never received the most up-to-date hard product installed on their latest Cathay 777-300ERs, sticking with the herringbone business class that has now been replaced everywhere else (except Air Canada, Virgin Atlantic and Air New Zealand). But the kind-hearted welcome and clean aircraft appearance suggested a machine in the prime of its life; most passengers would never have guessed it was three days from retirement.

Demonstrating the appeal of the Tokyo to Hong Kong route, with over twenty flights a day from Narita and Haneda every day, almost all of the 747’s 359 seats were occupied (breaking down as 9 first, 46 business, 26 premium economy, 278 economy) and we were ready to push back for an ontime departure at 1035 local time.

We made a long tour of the airfield, rolling past the Nippon maintenance hangars where the latest 787s received some attention, then out on a pier to the new runway 05 which extends into Tokyo Bay on stilts in the water. With a roar from the four massive PW4000 engines, we were rolling. After a thirty second race down the runway, the nose rose into the air and the whole machine levitated magically upwards. As Japan fell away beneath, we rolled into a series of turns to set course to the west for our four-and-a-half hour trip to China.

Soon after the seatbelt signs were switched off, a crew member announced that Mount Fuji was visible off the right side of the aircraft. I hopped out of my seat and found a free window on the other side, and there it was, rising 12,388 feet, the tallest mountain in Japan and in the words of UNESCO, “Inspiring artists and poets and the object of pilgrimage for centuries.” I’d seen it covered in snow before, but at the end of a hot summer, it was somehow futuristic and intimidating, this enormous yet mute black pyramid. Photos were snapped by passengers and then as Fuji-san slipped out of sight we settled down for an early lunch, served on trays in econony.

I had the Chinese beef option, which came with a prawn cocktail appetiser, a bread roll and a Kit-Kat, washed down with green tea and water. Although fairly basic, it was tasty and filling. Trays were cleared away and I sat back to read and listen to the dull roar of the queen of the skies cutting through the upper atmosphere at over 500mph, 35,000 feet above the East China Sea.

All too soon the distant thunder of the engines died away and a momentary sense of weightlessness signalled the top of descent into Chep Lap Kok airport. As our altitude on the flight map began unwinding, the captain came on the PA and announced that the 747s had only three days left to fly before being retired, paying tribute to the type’s long history in Cathay service and that the crew would be sad to see the end of passenger service for the jumbo – a classy touch.

Soon we were down in the haze of Hong Kong and the skyline came into view as the flaps were extended for landing. With a thump the wheels were lowered and we were on finals for runway 25R. We returned to earth with a rattle and a smudge of blue smoke whippinh out from under the wing. Spoilers rose to dump the lift and settle the full weight of the jumbo onto the wheels for effective braking; we smoothly decelerated to walking pace and turned off towards the bustling terminal area for parking, fifteen minutes ahead of our scheduled 1500 arrival time.

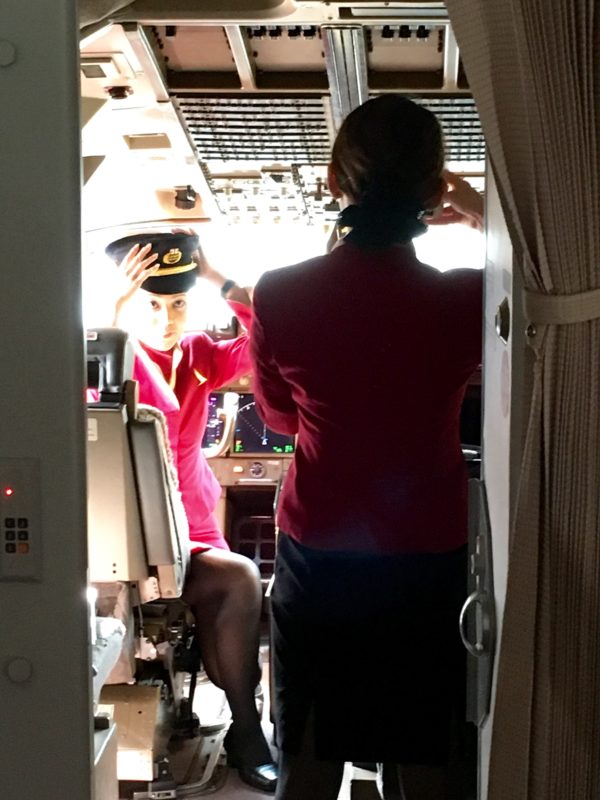

As passengers deplaned I asked if I could visit the cockpit and was escorted up the stairs to meet the pilots. We had a brief chat about the 747’s planned delivery flights to California and Bruntingthorpe UK for scrapping while the cabin crew took turns sitting in the pilots’ seats for photos as it was their last work trip on a jumbo.

The captain then invited me to sit in the captain’s seat for a photo of my own. I thought of all the men and women who had sat here during the hundred thousand hours B-HKT had clocked up since it was rolled off the line at Seattle in December 1992 for Singapore Airlines, and, since April 1997, Cathay Pacific – landings at dawn and dusk, long nights across the Pacific, daylight crossings of oceans, deserts, whole continents, in every imaginable weather conditions.

The last passenger flight, also CX543, operated as promised on October 1, a frenzy of avgeek enthusiasm and nostalgia for the end of an era. The following week, on October 8, Cathay operated a special sightseeing flight for 359 employees, each of whom donated HK$747 to the Hong Kong Breast Cancer Foundation, flight number CX8747, with the airline using social media to advise the public of the best vantage points to watch the aircraft fly over the city it had served for decades.

Twenty 747 freighters (six 747-400ERFs and fourteen 747-8Fs) fly on at Cathay but the era of 747 passenger flights at Cathay Pacific is over; my last trip on one was a memorable way to say goodbye. Thanks Cathay and thanks jumbo!

Since retireing to Thailand in 2005, Cathay has always been my fave for visits back to the U.S. BKK-LAX or SFO. Here’s hoping they fully recover from the current HK turmoil.

I well remember being at Boeing Everett Field in Seattle for the rollout of the very first Boeing 747-400 aircraft – it was not destined for CX – amidst great fanfare and enthusiasm from guests and manufacturing staff. A very memorable day of show biz presentation. I was privileged to work for the airline in Hong Kong for almost twenty years, much of it in the 747 era. Cathay Pacific’s entry to the 747 age was typically cautious, with the airline ordering just one 747-200, telling Boeing that if we like it and it works for us we will come back for more – which of course they did!

It was a wonderful experience of reading the article. Although, i didn’t travel with Cathay but after reading the article i felt like i travelled with them. Thumbs up. Carry on the good work.

Thanks for sharing the magic of the 747.

Great article, which really refreshes my memory of old time Hong Kong, and my time with CX.

CX is still my preferred airlines at LAX, if I have a choose to take them to Asia. I always feel I am back home once onboard a CX flight.