Braniff International was a big name in US airline transportation from 1930 until its bankruptcy and shutdown in May 1982. Starting out with Lockheed Vegas and Douglas DC-2s and DC-3s, the airline carved out a niche in Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas, and after WW2, won a South American route award that terminated in Buenos Aires. Mergers with Mid-Continent Airlines of Kansas City, and Panagra (Pan American Grace), a US carrier based in Panama, made Braniff International a US major.

In 1967 Braniff International caught the attention of the travelling public with a radical image makeover, steered by advertising executive Mary Wells: The End Of The Plain Plane. The staid red and blue cheatline was out, replaced by a striking new livery in which every plane was painted a different bold colour (initially seven, later 15 hues) with white wings. The colour schemes were used for lounges, ticket offices, ground equipment, and even the Jetrail monorail at Dallas Love Field airport. Art was flown in from Mexico and South America to complement the new look. Italian fashion designer Emilio Pucci created new uniforms, and Mexican architect Alexander Girard created a furniture line for offices and lounges, which was even made available to the public for a year. The brand refresh was a major hit and with the move to the new Dallas/Fort Worth mega-airport, the airline’s base became a hub.

With Texan swagger for bigger, better, brighter bolder, going supersonic was in Braniff’s DNA. As early as 1964, the airline had placed an initial order for the home-grown swing-wing Mach 3 SST, the Boeing 2707, going so far as to make industrial films explaining the supersonic future that awaited America in the skies. Alas the 2707 was too costly to take flight, and the programme was cancelled by Congress in 1971.

Supersonic Concorde Flying

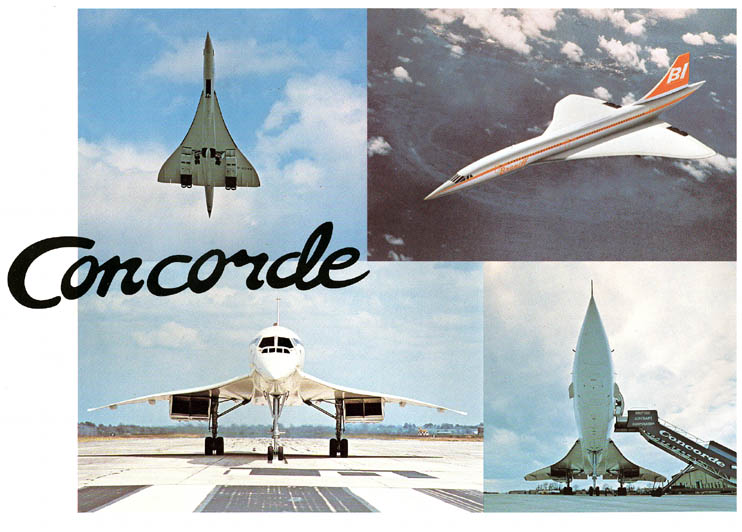

On the other side of the Atlantic, the British and French had joined forces to create a European SST, the Concorde. It was smaller (100 vs 277 seats) and slower (Mach 2 vs Mach 2.7), but undaunted, Braniff secured delivery positions for three Concordes in the late 1960s. It proved impossible to convert those options to firm sales, and finished machines were only delivered to British Airways and Air France, the flag carriers of the two nations that had created this miracle plane.

Concorde went into revenue service on January 21, 1976 with British Airways (to Bahrain) and Air France (to Rio via Dakar, followed by Caracas via the Azores). The market that best suited was across the Atlantic to the United States, but the European SST was banned from US skies, with citizen protests against aircraft noise cited by officialdom as the reason, although it is generally accepted that the lack of a homegrown equivalent also influenced the decision.

The first chink in the wall was chipped away when US Secretary of Transportation William Coleman granted Concorde access to Dulles airport, 26 miles west of Washington DC in rural Virginia; British Airways and Air France opened service from their respective hubs on May 24, 1976. However, the grand prize remained New York’s John F Kennedy airport, but even after the federal ban was lifted, New York banned Concorde flights locally until October 17, 1977, when the Supreme Court overturned a lower court ruling (it was pointed out that Air Force One itself, then a Boeing VC-137 aka 707, was louder at subsonic speed than a Concorde). Supersonic service to The Big Apple commenced on November 22, 1977.

This was a time of great optimism for the troubled Concorde project. British Airways and Air France were now flying the route for which Concorde was intended, and one of BA’s machines, G-BOAD, was painted on the left side in full Singapore Airlines livery and opened a service to Singapore via Bahrain with BA pilots and 50/50 BA-SQ cabin crew.

In fact the Singapore service only lasted three rotations due to complaints from the government of Malaysia about sonic booms in the Straits of Malacca, but G-BOAD retained the Singapore livery on its left side and was able to return to Singapore on January 24, 1979 using a revised departure routing off runway 02 at Singapore (Peya Labar) which avoided overflying Malaysia.

The Singapore Airlines partnership gave management at Braniff International ideas, whose ardour for supersonic flight hadn’t entirely cooled after the disappointment of the B2707 and its own early Concorde ambitions. Routes to Latin and South America (as celebrated by the famous “flying artwork” DC-8 painted by Alexander Calder) put the “International” in their name; perhaps they could now go supersonic down to Rio.

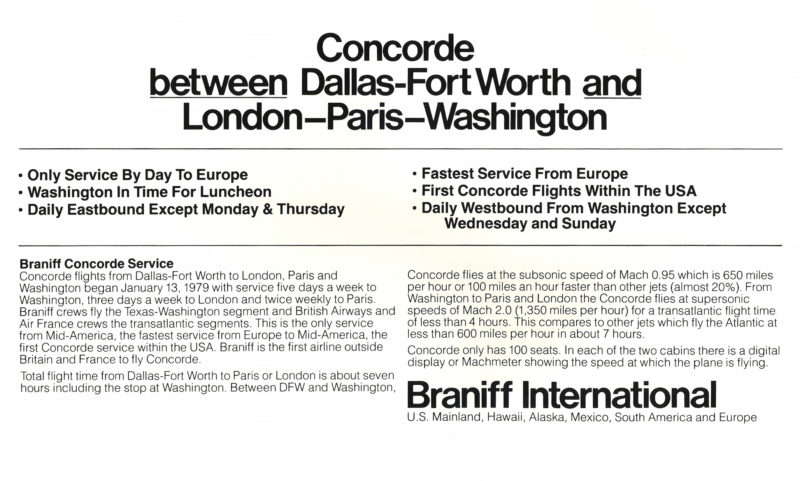

In lieu of ownership, a concept emerged for domestic Concorde services in the United States, to be operated by both British Airways and Air France planes, fresh in from the Atlantic, on the 1,172 mile (1,886 kilometer) route from Washington to Braniff’s home base at the new Dallas/Fort Worth airport. After a night stop, the aircraft would return to Washington the next morning in time to continue back to Europe. These would be Braniff flights with Braniff crews; the exterior identity of the aircraft – British Airways or Air France – would depend on the day of the week.

The only drawback was that, with the entire flight taking place over land, it could not operate supersonic due to the inability (to this day) to ameliorate the sonic boom, but cruising at a high Mach number of M.95 would still shave 20 minutes off the journey compared to a flight aboard a conventional subsonic airliner such as a Boeing 707 or 727.

The plan was helpful for all concerned. Washington flights struggled to make money for both British Airways and Air France, so hopefully this would create some feed for the transatlantic legs (Air France had already opened Washington to Mexico City in September 1978 with this intention; that route was mostly overwater and hence able to operate mostly supersonic, with a mid-trip deceleration to tiptoe across the Florida peninsula).

Other than the Singapore codeshare, Concorde hadn’t found any airline customers outside the borders of the countries that had created her. Now, with some marketing sleight of hand, another airline operator – Braniff International – could be claimed to exist.

And Braniff could offer a unique product – the excitement of flying on an SST – in a crucial period when making a big splash was vital, slugging it out with American and Delta in a never-ending turf war at Dallas/Fort Worth (“the Battle of DFW”) and with the deregulation of the domestic US air travel market just around the corner.

Pilot Training

A total of 14 Braniff pilots were trained in France and the United Kingdom – three captains, five first officers, four flight engineers, a check captain, and a check flight engineer. Those trained by Air France did their simulator course at Toulouse followed by circuits on a real aircraft at Shannon; those trained by British Airways did their simulator course at Filton in Bristol followed by circuits at RAF Brize Norton. Although Braniff’s initial plans were all over land and thus subsonic, Braniff crews were fully trained on type which included operating speeds of up to Mach 2.2.

As an aside, at the time, British and French pilots retired at 55, but in the United States it was 60 (today it is 65 on both sides of the Atlantic), which meant that a handful of the Braniff pilots who flew the Concorde would have been unable to do so in Europe.

Getting Around FAA Regulation

Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) rules meant that Braniff was not able to operate a foreign-owned and foreign-registered aircraft within the US, so the ownership of the Concorde that was operating on the day was transferred to Braniff on arrival at Washington. Both British Airways and Air France gave their planes new custom registrations to make a daily transfer to the “November reg” (N-) US register possible.

G-BOAA was rechristened G-N94AA so Braniff ground crew in Washington could then tape over the “G-“ to create N94AA. G-BOAB became G-N94AB and thus N94AB in Braniff service, G-BOAF became G-N94AF and thus N94AF, et cetera, for the whole fleet. (The only exception to the 94 series was G-BOAC which was G-N81AC.). Air France adopted a similar practise, with F-BVFA became F-N94FA and thus N94FA, F-BVFB became F-N94FB and thus N94FB etc.

The British or French documents certifying ownership, registration, and airworthiness were to be removed from the cockpit during the Washington turnaround and placed in a special compartment in the forward toilet, while US documents temporarily took their place up front for the trip to Texas.

Onboard the Concorde

The onboard product was lavish – five-ounce portions of caviar and Chateaubriand steaks washed down with Moet & Chandon bubbly, served on bespoke Braniff supersonic china. (Only the confines of the narrow Concorde cabin precluded the addition of bananas flambé or dry ice smoking from the aperitifs trolley, as in first class on subsonic Braniff flights.) The fare for the experience of flying on an SST was a flat $220 one way ($770 in 2018, adjusted for inflation), ten percent higher than a regular first class ticket.

To promote the new service, a tour of Braniff ports was operated by a chartered British Airways Concorde, calling at Memphis, Phoenix, Tulsa, Kansas City, Midland/Odessa and Oklahoma City. While British Airways and Air France expanded their charter operations in the 1980s and 1990s and visited some pretty obscure ports with their rocket ships, for some of the cities visited, the Braniff promo tour was their only Concorde visit – ever.

The first domestic commercial SST flights in the United States took place on January 12, 1979 from Dallas. Two Concordes had positioned in the previous day. After a ceremony in the crisp Texan winter morning in front of terminal 2W, N94AE (G-BOAE in disguise) departed at 0800 under the command of Braniff Captain Glenn Shoop, followed by N94AC (F-BVFC) under the command of his colleage, Captain Ken Larson.

After that, five trips a week were scheduled. Picking up an Air France Concorde at Washington, inbound from Paris, BN53 operated from the nation’s capital on Mondays and Fridays at 1910, landing in Dallas at 2100. BN189 was operated on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday with a British Airways machine, leaving Washington at 1840 and arriving in Dallas at 2030.

The aircraft would nightstop in Dallas and operate back to Washington the next morning in time to continue on to Europe later the same day. BN54 left at 0930 on Tuesdays and Saturdays, landing in Washington at 1300, final destination Paris, while BN188 left at 0830 on Wednesday, Friday and Sunday at 0830, into Washington at 1200, final destination London.

Braniff started flying their signature “Big Orange” Boeing 747-127 N601BN nonstop from Dallas to London Gatwick on March 18, 1978, so once the British Airways Concorde interchange started, Braniff could semi-legitimately boast of near-double daily service from Dallas to London: subsonic nonstop to Gatwick and supersonic one-stop to Heathrow.

Despite a number of doctored images being released of Concordes with a maroon cheatline and logo’d tail, no Concorde received Braniff livery. If one had been painted, it would presumably have been on one side, like G-BOAD, which provided free advertising for Singapore Airlines on its starboard side in the course of its Braniff flights long before their own services reached the United States.

Alas (and in hindsight surprisingly), this unique product failed to catch on with the American public. It is true that Concordes had a cramped interior, which only allowed economy-style 2-2 seating (albeit with generous legroom), compared to the more spacious accommodation available in the first-class quarters of a Boeing. The 20 minutes saved by cruising at a higher (though still subsonic) Mach number was judged to not be worth the discomfort. After the first few weeks, loads were normally as low as 20 passengers per flight, 20% of the available seating.

Thus the Braniff experiment was one more red herring in Concorde’s search for a sustainable supersonic business model. It was worth a try – a stronger economy or a different market reaction could have resulted in Braniff buying Concordes for service to South America (just as the codeshare with Singapore Airlines might have resulted in sales and a supersonic Singapore – Hong Kong – Tokyo corridor).

Before the story ends – one important question remains. Did Braniff flights go through the sound barrier? Even though they planned for Mach 0.95, it isn’t considered controversial to suggest that most pilots – and thus passengers – joined the supersonic club for a few seconds or minutes over Tennessee or Arkansas. Wouldn’t you?

The End

With passenger numbers showing no sign of getting anywhere near break even, the airline had no choice but to bow to the inevitable. The supersonic era on domestic flights in the United States ended on June 1, 1980.

Air France pulled its Concorde service from Washington in October 1982, while British Airways was able to add a reasonably successful tag to Miami in March 1984 which kept the route in business for a decade, albeit was only bookable by international passengers originating or ending their journeys in London. Miami lasted until March 1994, and Washington ended in November of the same year.

Interestingly, in the middle of that period, British Airways added a second tag from Washington in June 1988 (also only bookable for international passengers): to Dallas no less. Alas passenger numbers weren’t any better the second time round, and the route was axed after only four months.

Braniff International itself only lasted a few more years after its Concorde experiment. While the 1970s had seen success and style in equal measure, the scale of the airline’s expansion at the dawn of deregulation was too much to handle – hundreds of new route applications including pushing out east into mainland Europe, and west across the Pacific to Japan, Hong Kong and Singapore, all with a fleet of cavernous Boeing 747s. The airline was the first big casaulty of the deregulation era, making headlines around the world when its 71-strong rainbow fleet ceased operations on May 12, 1982.

Braniff failed in spectacularly glamourous and stylish beauty (they loaded so much caviar onto Concorde flights that cabin crew would take leftovers home and feed it to their cats). While occupied with such pie-in-the-sky ideas as subsonic Concorde flights and half-empty bright orange 747s to Singapore, Robert Crandall at American Airlines was applying computer power and forensic analysis to manage yield and weaponise pioneering AAdvantage frequent flier programme. With hindsight, the outcome of the Battle Of DFW was never in doubt.

Nonetheless, by a complex arrangement with two European airlines, Braniff was able to provide the American travelling public of the unique excitement and prestige of flying on an SST. Because it didn’t last doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. Forever flying colors.

Thank you for this story. My father, Francis Rauch, was a pilot with Braniff (all iterations). I remember him taking me to DFW from our home in East Texas to see “Braniff’s Concorde”, or to me as a very young boy, “the nose plane”. I remember being at the DFW terminal being directed where to look for the landings, taxi and gate arrival of some of those early flights. I can only recall one departure, though… I will never forget the first time I saw Concorde come up to the gate with the nice pointed down and the strange looking windscreen. Such an amazing plane. A couple more notes, we had some of the Braniff lithographs with the BI livery and I even had a small toy Concorde with a prop on the back as a little mobile near my bed, too.

Brian Rauch

Texas

I flew this Braniff Concorde from IAD to DFW in May 1980 but it would be two decades before I got to experience the plane at supersonic speed!

At age 32, I was the youngest of the 17 Braniff pilots to fly Concorde, becoming the youngest Concorde pilot in the world. I am now 75 years old, the only surviving Braniff Concorde pilot. I went on to fly for US Airways for 25 years and retired as a Captain for American. I took Concorde training in Toulouse, France in 1979 and remember my Concorde experiences as if it were yesterday. This was a great article. Thank you for remembering Braniff and its Concorde service. John Baganz

Thank you for this! My grandfather was an airline mechanic after retiring from the USMC, and worked for Braniff at D/FW for years – even married his second wife at the chapel there!

Many thanks for an interesting article on my favourite aircraft of all time.

I was extremely fortunate to actually site a Concorde performing a low level low speed flight over the city of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia some fifty years ago. I was on the tenth floor of the then Commonwealth Centre so had a fantastic view.

Awesome article. I here in Miami I remember all the landings and take off from Air France’s Concordes. It was always a big crowd at the end of runway on the East side of Miami International. I used to work on a Catering company so we hang around to watch it. Great times sadly they won’t come back. Hope for the new SST , United is the first US carrier to buy them. Future is here.

Thanks to John Koury and Maurice Askew who delivered us useful information about Concorde utilization in USA !

Great story about a great airline. So sad they didn’t survive. I got to witness the landing and takeoff of Concorde at Midland-Odessa, MAF. A bunch of us took a long lunch break to see the only visit it made to West Texas. Unforgettable!

My late brother in law saw the Concorde fly into Memphis International Airport. He was working at Delta Ford Heavy Trucks located by the airport when his boss ordered everyone outside to watch the Concorde land. They stayed after business hours just to watch it takeoff. Federal Express (FedEx) was looking at the possibility of using Concorde for cargo flights.

Excellent and nostalgic article. Many thanks.

I would add one important point. In recent declassified records it emerged that President Kennedy, in a conversation with then FAA Administrator Najib Halaby, ordered Halaby to ensure that no US carrier (Pan Am, AAL, etc) would be allowed to acquire any Concorde aircraft so that the US SST program would move forward.

John Khoury Esq

Thank you for this wonderful review of our Concorde service. Just a couple of things: the End of the Plain Plane Campaign began in 1965; Alexander Girard was from New Mexico and our 1978 Concorde Orange Ultra Color Scheme would have featured an orange stripe down the left side.

As a French, I did not know exactly the way Concorde was used in the States.I Thanks to Sam Chui to refresh up our mind with this excellent Charles Kennedy’s report !

Well researched and in depth article by Charles Kennedy, Thank You!

Contains much information had not read about before and excellent rare photos and video.

An insightful look into the exciting and troubled aviation world of the past that is too quickly forgotten.

Braniff was indeed a trail-blazer and like Pan Am, part of the old school of how airlines should be operated.

However with their noble philosophy of full service, high standards and ambitious and often risky strategies, they ironically became two of the earliest, and largest, victims to deregulation and the rapidly changing dynamics of the airline industry at the time.

wow I never knew this about Concorde and I didn’t know Singapore airlines “kind of”operated one.