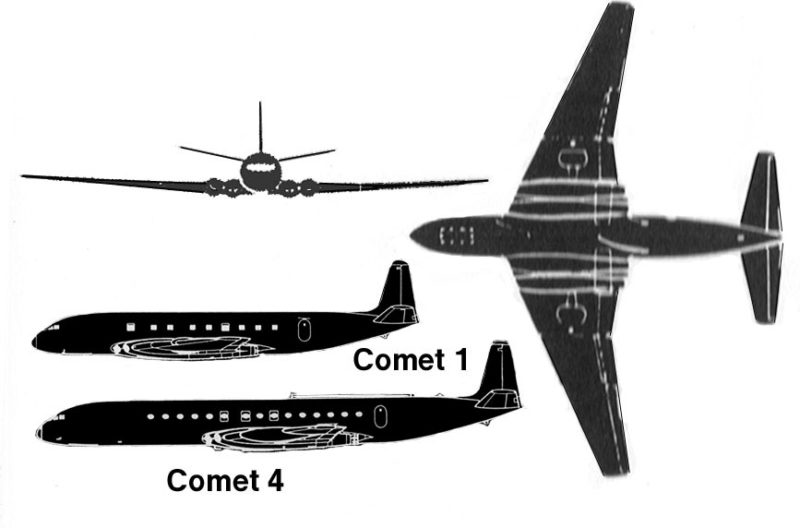

Britain’s de Havilland Comet 4 introduced jet travel to the North Atlantic on October 4, 1958, fifteen days before the USA’s Boeing 707.

The historic day followed the saga of the Comet 1, which had introduced jet transport to the world on May 2, 1952 and was soon flying the world’s airways as far afield from London as Tokyo, Singapore and Johannesburg. Alas, de Havilland’s pioneering steps were unrewarded as 1954 was marred by a series of mid-air disasters and the grounding of the Comet; the groundbreaking investigation introduced the world to the concept of metal fatigue.

Thus the Comet 4, pride of the fleet at the British Overseas Airways Corporation, or BOAC, Britain’s then-long haul flag carrier, which resides in a lineage preceded by Imperial Airways (before 1940) and leading to British Airways (after 1974). In the years from 1958 up to BOAC’s retirement of the Comet 4 in 1966, its fleet of nineteen pioneering jetliners flew out of the United Kingdom to every corner of the globe – Africa, the Middle East, the Indian Subcontinent, across Asia to Japan, Australia and out into the Pacific – New Zealand, Fiji, Honolulu.

Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT)

CFIT is one of the most well-used acroynyms in the business of air crash investigation. It stands for Controlled Flight Into Terrain, and has proved to be one of the most diffcult accidents to eliminate. As BOAC introduced the world to the Comet 4 and air travel to the world at the dawn of the jet age, they left tyre tracks across a game park in Kenya, a trail of sparks at both Stansted in Essex and Rome, stripped trees of their leaves in Rome (again), and reduced the elevation of a hill outside Madrid by a foot or so. That not a life was lost nor an injury suffered in any of these five serious incidents must represent the luckiest streak in the history of commercial aviation.

1-2: Rome & Stansted

Unconventional descent profiles used by early jet crews to enter the circuit were known as Jet Penetration, and would now be impossible due to the volume of traffic. A high speed, power off descent would take the plane down to 4,000 feet, which would then be flown level until the speed washed back to 170 knots, the maximum speed for flaps forty. Flaps forty without the landing gear (wheels) down would trigger a configuration alarm, which would be reflexively cancelled by one of the pilots. Closer to touchdown, the gear would be extended without reminder from the silenced cockpit systems.

Captain Peter Duffy, author of Comets Concordes (And Those I Flew Before) illustrated the lack of Cockpit Resource Management (CRM) of the era, the inability of junior airmen to question the judgement of those more senior. He wrote of a flight into Khartoum, Sudan, where the check pilot in the left seat asked him to perform such an arrival, under the check pilot’s instructions. “I was a little doubtful about adopting this non-standard and unauthorised procedure, although it was within the permitted performance envelope, but curiosity prevailed, supported by a desire to avoid upsetting him by a refusal.”

Dysfunctional cockpit dynamics and vague procedures meant an accident was inevitable, and it happened in Rome at the conclusion of a flight from Beirut. The belly landing and ground slide was so gentle that everyone outside the cockpit thought the landing had been normal, on its gear, not its exposed underside. As the engines became silent, a flight attendant opened a door, and was amazed to see a fireman standing outside on the grassy surface at the runway’s edge, and only a feet below the height of the door sill.

No one was hurt but a verdict of pilot error was granted by the investigation, although the trap was laid in the form of a lack of operating rules in a primative era. And to prove the point, another BOAC Comet 4 performed an identical ground slide on its belly at Stansted, in the Essex countryside, a few months later, during a training sortie.

3. Nairobi

This incident could have been a major air disaster of the era – descending in a jet until blindly hitting the ground in the countryside outside Nairobi must surely result in an instant and fiery demise, and that these passengers and crew lived to tell the tale is a deliverance rarely allowed in aviation.

On an otherwise normal night arrival in December 1959, the captain’s altimeter was set to 938 milibars of barometric pressure instead of 839, causing the instrument to read 3,000 feet higher than the ship’s true altitude above sea level. This was the kind of pilot error which would have been instantly caught in a later incarnation of cockpit procedures where the value of teamwork and crosschecking each other’s work was better understood.

The brand-new Comet 4 made a perfect touchdown (on its extended landing gear) in Kitengele game park, a large area of hard flat grassland surrounded on all sides by vast expanses of lethal trees, rocks, crevices and ridges. The captain was allowed a one-in-a-billion chance to apply full power, raise the nose and fly away, and make a safe landing.

4. Rome again

The crew in the next incident were not at fault, but it does illustrate one of the challenges aviators faced in the early years of the jet age – poor ground-based navigation aids. The venue was once again Rome. The radio beacon at Ciampino airport shared a frequency with a much more powerful transmitter elsewhere in the Mediterranean, under some atmospheric conditions enough to divert the indicated heading towards high ground. The problem had presumably resulted in dangerous proximity to terrain previously, but never was a flight brought so close to disaster as this BOAC Comet 4. Navigation radios were tuned and headings faithfully selected but their actual course was towards disaster.

Rushing trees and stony ground materialised in the landing lights. Before the pilots could react, the jet plowed through and was able to fly on to a safe landing. All four Rolls-Royce Avons ingested branches and leaves, but there was no damage sustained by the aircraft or its engines once the twigs had been plucked out of the landing gear. Another lucky escape!

5. Madrid

The final incident was similar and tested the Comet 4’s strength beyond doubt a few months later, on the night of March 14, 1960, on a hilltop outside Madrid. G-APDS was coming in from London, and after transitting the Spanish capital it was bound for Santiago de Chile via Dakar, Recife, Sao Paolo and Buenos Aires. The crew were attempting what was later known as a ‘black hole’ visual approach, where there is no light or other visual reference between the aircraft and the distant runway. Blackhole approaches claimed a number of early jets until it was realised that it was close to impossible to do safely without guidance from approach lighting or instruments.

As the descent profile sagged below the desired glideslope, a ridge loomed out of the darkness, too late for evasive action. The jet smashed onto the very summit of the ridge. On the underside of the engines were emergency cut-off switches, and the impact triggered the shutdown of both port engines. Having ripped off the fuel tank from the left-wing, and the left main landing gear, the ground then fell away precipitously, launching the aircraft into space, trailing a plume of metal, tree, rock, soil and smoke. With full power from engines three and four, and a lot of aileron and rudder, the wounded jet circled to land on a different approach, and after extensive repairs, returned to service.

Look to the Future

Other BOAC Comet 4s had scrapes, notably G-APDB which was substantially damaged in Cairo on August 22, 1960, after an aborted takeoff on a closed runway, losing a couple of wheels in an excavated hole at fifty knots; and G-APDN which suffered a tailstrike at Tehran on March 9, 1964 so heavy that it disabled the elevators and the rest of the landing was without pitch control. But these were within the normal realm of knockabout early Jet Age runway scrapes and can’t compare with striking a hillside in midflight, or a blindfolded touch-and-go in the Kenyan high plains.

As well as providing interesting anecdotes, close encounters with disaster bring to light failings in aircraft, procedures, ground aids, maintenance and piloting without the cost in blood and treasure of having the real thing. These incidents certainly contributed materially in the evolution of airline safety – the need for more rigid cockpit procedures, the abandonment of black hole approaches as something to even be attempted, better navaids. The gear-up landing in Stansted had another unintended benefit – repairs to the belly revealed corrosion caused by the use of Redux adhesive that would have not otherwise been discovered, and resulted in modifications to the entire worldwide fleet of Comet 4s. Humans are a winged species, and incidents such as these are the way we have learned to be so with safety and confidence.

Cover Image: Wikimedia Commons/Ken Fielding

I was on a Comet flying back from Bahrain in the 1960s when we were told that there was a fire in one of the engines and we had to make an emergency landing at Damascus, There was no fire but they had to clean out the engines after fire extinguishers had been discharged into them – the so-called ‘fire’ was a false alarm. But we spent a pleasant few hours being looked after in a city hotel!

I remember the Comet night touch-and-go in Nairobi game park, because there were photos in the next day’s East African Standard of the wheel tracks and of the Comet at Nairobi airport with a thorn bush in its undercarriage.

BTW, I believe that the radio altimeter was suspect. Even though it was warning the crew of their proximity to the ground (especially when they went over the Ngong Hills on the Rift Valley escarpment), they trusted the pressure altimeter over the radalt.

Does anyone know where I could obtain the accident report or the East African Standard article?

Sam. Enjoy your reports.

Comet IV will be a lfe long memory. As a child grew up across Juhu Airport (smaller airport= largest aircraft to use it was DC 3).My dad was an Aviation pioneer in India, had a 2 plane air service out of this airport. JRD Tata alo started out from thi airport.

One morning (early 1950s)I was at the window looking at the airport and the runway ( E-W) when this huge airplane was landing in our direction! Saw it swerve a little, left wheel was in the grass and it slowed down but kept coming….the pilot braked hard etc and swung it to left to a 90 degree angle and it stopped. Had it continued it would have crossed a couple of ditches, cross a busy main road and struck a number of houses!

People were taken off. Story was the pilot mistakenly took it as his landing strip/airport of Santacruz International airport ( now CST airport). Runways were /are in same config.)

It stayed there for more than two months, was a tourist attraction! Date it will take off was announced, thousands of people watching and it took off in a mighty roar (W to E) over the ocean!

Something I would NEVER forget.

Enjoyed reading about British Comet. 1967 I few from Mexico City to Los Angles Ca. But had to make a stop on Mazatlán. Maintenance problem. Mexicana Airlines.

Another wonderful and informative Charles Kennedy historical insight. I, and probably many others, assumed that Comet’s days were over after the series of catastrophic metal fatigue induced mid air break-ups.

Was unaware that its ghost re-appeared as Comet 4 and, even more surprisingly, was in operation until well after the introduction of the far superior B707.

Those aviators in aircraft like Comet must have had nerves of steel and ‘flying instinct’ of supreme proportions to keep those stricken aircraft as described above from total loss.