On August 24, 2001, an Air Transat Airbus A330 performed the longest-ever glide on a commercial aircraft before landing in the Azores. Without engine power, the aircraft glided for nearly 75 miles or 121 kilometres. Both Rolls-Royce RB211 Trent 772B engines flamed out when the aircraft was 65 nautical miles from Lajes Air Base. After what could have become one of the severe incidents, the aircraft was nicknamed the “Azores Glider”.

Flight Details

The Airbus A330-243 with registration C-GITS was performing Air Transat Flight 236 from Toronto-Pearson International Airport, Ontario, Canada to Lisbon Airport in Portugal. A total of 306 people, including 293 passengers and 13 crew members were on board. The crew consisted of Captain Robert Piché (43-year-old), who had 16,800 flight hours, and First Officer Dirk de Jager (28-year-old), who had 4,800 hours of flight time. Captain Piché is also an experienced glider pilot.

The catastrophic situation in which Air Transat Flight 236 found itself was caused by a fuel leak when the aircraft was over the Atlantic. The investigation found that the fuel leak was due to a problem in the maintenance of the aircraft. It was concluded that an incorrectly installed component didn’t leave sufficient clearance between the fuel and hydraulic lines.

Leaving the gate at Toronto-Pearson, the aircraft had 46.9 tonnes of fuel on board, 4.5 tonnes more than required by regulations. Flight 236 took off from Toronto at 00:52 UTC. Almost four hours into the flight at 04:38 UTC, the aircraft began to develop a fuel leak from its no. 2 (right) engine. Following the fuel leak, the crew noticed low oil temperature and high oil pressure on engine no. 2. However, the crew suspected it to be a false warning and informed it to Air Transat maintenance control centre in Montreal, which later advised them to monitor the situation.

Severe Fuel Leak and Imbalance

At 05:33 UTC, the crew received a warning of fuel imbalance. As the pilots were unaware of the fuel leak through the fractured fuel line, the crew followed a standard procedure to remedy the imbalance by transferring fuel from the left wing tank to the right one. The right fuel tank was leaking at about one gallon per second and the entire transferred fuel was also lost. Unable to maintain the fuel balance, the crew decided to initiate a diversion to Lajes Air Base in the Azores at 05:45 UTC. They declared a fuel emergency with Santa Maria Oceanic air traffic control three minutes later.

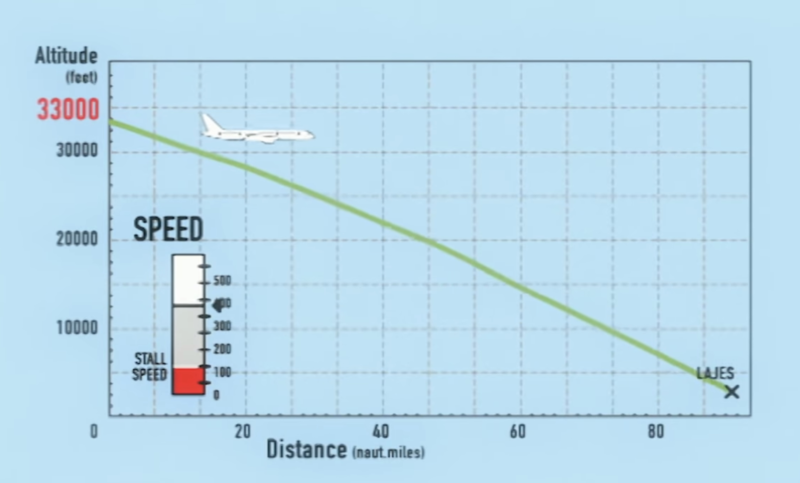

En route to Lajes, the right engine flamed out at 06:13 UTC followed by the left engine after 13 minutes due to fuel starvation. The aircraft was at FL345, 65 nautical miles from the Lajes airport, when its both engine flamed out. The crew initially reported that ditching at sea was possible.

The emergency Ram Air Turbine deployed automatically to provide essential power for the aircraft’s critical sensors and flight instruments to fly the aircraft as well as enough hydraulic pressure to operate the primary flight controls. Five minutes later, the oxygen masks dropped down in the passenger cabin.

Steep Descent

Assisted by military air traffic controllers and radar vectors from Lajes ATC, the crew carried out an engines-out, visual approach, at night and in good visual weather conditions. The aircraft was descending at about 2,000 ft/min (610 m/min) and the crew calculated that they had about 15 to 20 minutes left before they would be forced to ditch in the ocean. However, the air base was sighted as an alternative a few minutes later. Captain Piché executed one 360° turn, and then a series of “S” turns, to dissipate excess altitude during the engine-out glide.

After gliding for nearly 75 miles or 121 kilometres, the plane touched down hard in Lajes, around 1,030 feet (310 m) past the runway threshold of runway 33, at a speed of around 200 knots at 06:45 UTC. Following the touchdown, the aircraft bounced once, and then touched down again, roughly 2,800 feet (850 m) from the threshold. Maximum emergency braking was applied and retained, and the plane came to a stop. After the aircraft came to a stop, small fires started in the area of the left main-gear wheels, but these fires were immediately extinguished by the rescue response vehicles that were in position for the emergency landing.

It was concluded that the Captain’s skill in conducting the engines-out glide to a successful landing averted a catastrophic accident and saved the lives of all those on board. The First Officer provided full and effective support to the Captain during the engine-out glide and successful landing.

The Captain ordered an emergency evacuation; 16 passengers and two cabin crew members received injuries during the emergency evacuation of the aircraft. The plane suffered structural damage to the main landing gear, mainly due to the hard touchdown and the lower fuselage, both structural deformation from the hard touchdown and various punctures from impact by pieces of debris shed from the main landing gear.

Captain Piché on the 20th Anniversary of Flight 236

Twenty years after having achieved the longest-ever glide on a commercial aircraft, which is described as “the greatest feat of the last 50 years in civilian piloting” by the Air Line Pilots Association, Captain Robert Piché noted that not everything has been said about the incident.

“The question I ask myself now, in 2021, is, what does the future hold for me? The lesson I learned from this is that anything is possible. Even if you plan, the best and the worst can happen. I’m not looking forward to growing old, but I can’t wait to see what life has in store for me.”

“I was put on a national hero pedestal, so people don’t think I was scared. But I am a human being like everyone else. I was the first to be afraid.”

Captain Robert Piché

“When I tell people that I was scared, they don’t want to believe me, they think I’m saying that out of modesty,” Robert Piché explained in a telephone interview.

The aircraft was repaired and returned to service in December 2001, with the nickname “Azores Glider”. It was in service with Air Transat before being placed into storage in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. On October 18, 2021, the aircraft operated its last flight with Air Transat and was subsequently returned to the lessor AerCap.

Feature Image: “FAA”