Approaching midnight on June 28, 1998, a United Airlines Boeing 747-400 lost one of its engines shortly after lifting off from San Francisco International Airport. While recovering from the engine failure, the jumbo jet came within 100 feet of crashing into San Bruno Mountain and nearly stalled. It was approaching San Bruno Mountain so closely that air traffic control radars briefly stopped detecting the aircraft for 15 seconds, igniting controller fears that the aircraft had crashed.

The aircraft was vectored to dump fuel over the Pacific Ocean before it eventually returned to San Francisco for an overweight landing. Flight 863 prompted United to change its pilot training requirements, which ultimately became industry-wide standards.

Flight Details

The Boeing 747-400 was performing United flight UA863 from San Francisco International Airport to Sydney International Airport with 288 passengers and 19 crew members on board. Flight UA863’s captain had more than 23,000 flight hours whereas the F/O had 9,500 flight hours in his log book. They were accompanied by two relief pilots in the cockpit. The first officer was the pilot flying who was just out of practice, having made only one takeoff and landing in a 747 during the year preceding the incident.

Flight UA863 lined up with runway 28R on a foggy night at SFO. Given that the visibility was good despite a foggy night, the F/O pulled back on the yoke taking off for a long-haul flight bound for Sydney a bit past 10:30 pm local time. However, shortly after takeoff, the pilots experienced loud thumping noises accompanied by small vibrations from the aircraft at approximately 300 feet (90 m) above ground level. Having just taken off, the pilots thought that a tire might have exploded but as they retracted the gear the exhaust temperature on the number three engine started rising. The exhaust gas temperature of the number three engine rose to 750 °C, exceeding the takeoff limit of 650 °C and the crew were having a compressor stall on the engine.

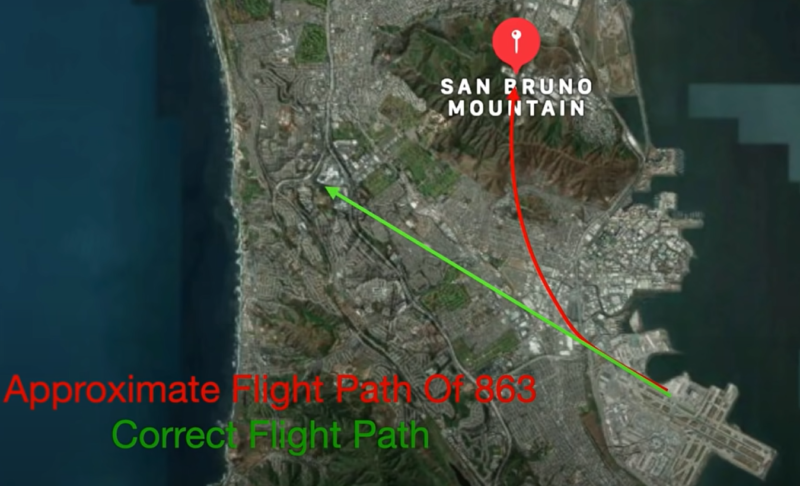

Following the surge in the vibrations, the captain retarded the number three engine throttle to idle, which stopped the temperature rise and the aircraft vibration went down. However, due to the imbalanced thrust, the jumbo jet started to yaw towards the right, resulting in a dangerous loss of terrain separation. Banking alone, however, was insufficient to control the vertical “yaw” axis, and the aircraft entered a skidding right turn that led directly toward San Bruno Mountain. To compensate for the imbalance, the F/O applied the aileron. Instead of an aileron, the use of a rudder would have been the correct response to compensate for an asymmetrical thrust condition. The ailerons control the aircraft’s longitudinal “roll” axis whereas the vertical “yaw” axis is controlled by the rudder.

Captain: “United 863 heavy, we’ve lost an engine, we’ll be proceeding out the 295 and returning to the airport.”

Shortly after, the relief pilots noticed that the aircraft had lost approximately 40 knots indicated airspeed after the problems with the engine and shouted ‘airspeed’ to the F/O to alert him to the potential stall danger, as the 747 was dangerously slow. At that point, the stick shaker system activated indicating that the aircraft was very close to a stall and the captain took over the control of the aircraft. The non-flying pilots were handling the checklist during the emergency.

As a result of the imbalanced thrust, the aircraft drifted to the right and narrowly avoided colliding with San Bruno Mountain. In order to do so, the captain held the aircraft level to increase the airspeed, and also to avoid a stall. The 747 had received a terrain warning as it headed towards the mountain which rises to an elevation of 1,319 feet. Furthermore, the use of ailerons also deployed spoilers on the down wing, which increased the jet’s net drag and decreased its net lift. The best way to avoid a stall would be to drop the nose so that the plane could gain some airspeed but doing that would send the aircraft right into the mountain.

Flight UA863 Disappeared Briefly On Radar

Given that the aircraft’s speed was so low, the controllers could no longer see the plane on the radar. But, approximately after 15 seconds, the plane was back on their scope.

Controller 1: “…Is United 863 still…Oh there he is, he scared me, we lost radar, I didn’t want to give you another airplane if we had a problem.”

Controller 2: “Are you gonna keep him, or are you gonna give him back to me?”

Controller 1: “Nah, he’s supposed to be on you isn’t he?”

Controller 2: “I haven’t heard from him.”

Controller 1: “Okay, I’ll try him again.”

With cockpit warnings signalling an imminent crash, the captain carefully put the jumbo jet into climb trying not to stall the aircraft and cleared the mountain reportedly by a few hundred feet.

After the near-collision, flight UA863 climbed to 5,000 feet and the controllers gave the vectors to dump the fuel over the Pacific. After the aircraft had shed quite a bit of weight, (approximately 84 tons of fuel was dumped) the jumbo jet returned to San Francisco for an overweight landing.

Captain: “We do want equipment standing by just as a precaution. Souls on board three zero seven.”

Flight UA863 landed safely on runway 28R avoiding any further incidents and none of the 307 people on board sustained injuries. Residents in houses along the flight path, in South San Francisco, Daly City, and San Francisco, called into the airport to complain about the noise and voice their fears the jet was about to crash.

Aftermath

Afterwards, it was discovered that the plane had cleared the mountain by the smallest of margins as there were television and radio towers on its summit. Had it been unable to climb a few feet, it would have crashed into the mountain.

In a situation like this in which flight UA863 found itself, pilots are trained to counter the yawing motion caused by thrust asymmetry by using the rudder instead of ailerons. In this case, the F/O was just out of practice as he had only made one takeoff and landing in a real aircraft in the past one year. This means that when the F/O did pilot the flight UA863 that day, he was doing it for the first time in almost a year. However, in such long-haul flights its common that the takeoffs and landings are split between a pool of pilots meaning that each pilot gets fewer opportunities to practice their takeoff and landing skills in a real aircraft (they do practice in simulators though!) rather than on a narrow-body jet.

According to Mark Swofford, who was United’s 747-400 human factors accident investigator and a 747-400 fleet Standards Captain at that time, the first officer’s use of aggressive roll control raised the left wing roll spoilers contributing to drag and dangerously slowing the aircraft. As reported by Swofford, additional contributing factors included; the Captain being slow to take control, poor recognition of the skid by the crew, slow recognition of the engine compressor stall by the crew, poor tracking and, very aggravating to the FAA, United’s failure to report the incident, as required.

United revised its training protocols after the incident, with a special focus on getting co-pilots more hands-on flying time, which ultimately became industry-wide standards. United reconstructed this flight in a simulator and it was shown to all 9,500 of the airline’s pilots. They also increased the frequency of refresher training for 747-400 crews from once a year to twice a year. United also mandated that pilots would require to make at least three takeoffs and landings in a 90-day period, of which one of them had to be in an actual aircraft. The airline submitted some other corrective actions to management and the FAA, including specific simulator training on compressor stall recognition and corrective action using the exact same conditions, which were accepted.