The ditching of USAir 1549 in the Hudson River was ten years ago today. Can you believe it? Here’s a little refresher, and my experience of spending a day with the pilots a year later.

First, the flight. All 150 seats on the Airbus A320, registered N106US, were full for the 2h trip from New York’s La Guardia airport, a small and crowded airport close to Manhattan only used for short flights, to Charlotte in North Carolina. It was -7C with snow on the ground, and the water in the nearby Hudson River was 5C. At the controls were Captain Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger and First Officer Jeff Skiles. The three flight attendants in the passenger cabin had a combined experience totalling 95 (NINETY-FIVE) years.

At 1525 US1549 was cleared for takeoff; two minutes later, climbing through 2,818 feet and after covering 4.5 track miles, they hit a big flock of migrating Canada geese, many of which were ingested by the engines, which both failed. Momentum carried the plane up to 3,060 feet before they ran out of energy and started descending. Air traffic control suggested a return to La Guardia, or Teterboro, a nearby executive airport in New Jersey, but both were out of reach. They passed over the George Washington Bridge at 900 feet and splashed down in the Hudson River at 1531 after only six minutes in the air, half of it without engine power.

As the plane approached the water, someone in the back yelled out, “Exit row people get ready!” Very New York. At the other end of some kind of experience spectrum, I met one passenger who regained his senses standing in the aisle but thought he’d died in the crash and looked back to his seat to see what his dead body looked like, and only realised he’d survived because the seat was empty. (Jesus Christ.)

Ditching a plane in water is considered to be a non-survivable event (although there have actually been successful precedents, most notably an Aeroflot Tu-124 that lost both engines and landed in the Neva River in Leningrad/St Petersburg in 1963, and was towed to shore with all the passengers aboard, who then escaped through a hatch in the roof).

The last passenger was rescued at 1555, 24 minutes after the crash. Sully walked up and down the aisle of the sinking plane twice to make sure everyone was off. The successful outcome for US1549 was due to a combination of events. It was daylight, and the cloud base was high (around 4,000 feet) so the pilots stayed visual with the ground. Sully’s excellent flying of the plane – and fantastic teamwork in the cockpit with FO Skiles. The Airbus fly-by-wire system that kept the plane from stalling. The air traffic controller who alerted the Coast Guard before the plane was even in the water. The very experienced cabin crew. The passengers who stayed calm. The structural strength of the plane which stayed intact after the impact with the water. The ferry and riverboat operators who were able to reach the scene quickly to rescue the passengers.

The passengers got $5,000 each and a refund of their ticket, and later a second payment of $10,000 if they promised not to sue. The plane was moved to a warehouse in New Jersey for the investigation, and then sold to the Carolinas Aviation Museum in Charlotte to create a new centrepiece for their collection, which includes a Piedmont DC-3 and a bunch of interesting military stuff. Which brings us to part deux.

In June 2010, dear comrade Roger Jarman of Atlantic Models was in a partnership running a newly-restored Douglas DC-7B propliner from the 1950s in Eastern Airlines livery. When he heard that the A320 was going to be unveiled in its new permanent home, he offered the DC-7B to transport Sully and Skiles to Charlotte for the event. Turns out Sully as a kid was very keen on the DC-7 and Eastern Airlines and asked if he could fly it there. So he and Skiles went up with an FAA examiner and did a dozen touch-and-goes each in the plane to get their DC-7 typeratings, and on June 11, 2010, the 50-odd seats were filled with enthusiasts, media, and a few US1549 passengers. Jeff Skiles was at the controls, and on his birthday too (alas the DC-7B’s insurance company said Sully wasn’t allowed to fly it, can’t remember what their logic was).

When I saw them on the TV after the accident, Sully seemed serious and intimidating, whereas Skiles was witty and self-deprecating, so I imagined Skiles would be much more approachable in real life, but I actually found his humour to be a defensive wall (although he is very funny), whereas Sully was engaged and curious and we had a couple of really good chats about his time in the UK flying Phantoms for the USAF out of Lakenheath, US1549 (beancounters at USAir had introduced new emergency checklists without tabs to save money, and it hindered their troubleshooting on US1549), and the state of the airline business today (I suggested modern air travel is crap compared to the era of the DC-7B and he argued the opposite, that airfare comparison websites had made it possible for airlines to pitch the product at exactly the price the market will bear, in other words modern air travel might be crap but it’s our fault for being cheapskates).

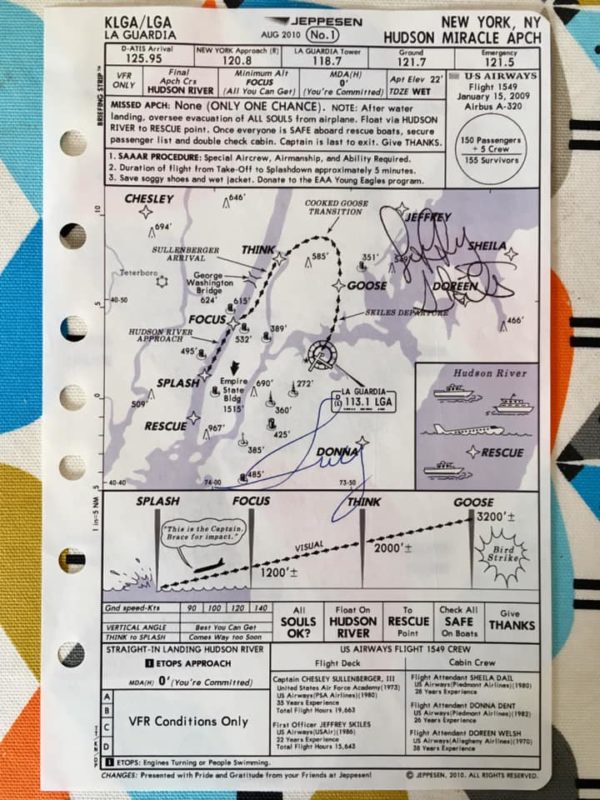

It was a good day for memorabilia. Jeppersen, who produce maps for aerial navigation for the whole world, produced a special approach map (“plate”) for the US1549 ditching, and I got mine signed by both pilots, surely an incredibly rare piece of memorabilia. And I won a beautiful model of our DC-7B made by Atlantic Models, with each wing signed. That was pretty amazing! You can see me holding it in one of the photos.

Highlight of the event at the Carolinas Museum was an old boy in his 90s who brought his pilot’s logbook to show us that he’d flown our DC-7B as an Eastern Airlines captain in the 1950s (he retired off the Tristar aged 55 in 1980) and told me how much he’d enjoyed flying Mustangs in combat out of the UK for the USAF in World War 2. I would have thought that was terrifying but he seemed to have had a great time – indestructable, late teens, boozing and shagging all night in London then grabbing a mail train back to an airfield in the English countryside, jumping in a Mustang and going to kill some Nazis.

The A320 that went into the Hudson is as famous as Sully, it was interesting to see the dents in the nosecone and wing leading edges where the birds hit (a Canada goose weighs 5kg). Sully sat in the captain’s seat and instinctively adjusted the seat. “It did its job,” he said. The museum have created an exhibit about the flight including a banged up catering trolley from the rear galley still full of Coke cans flattened by the impact with the Hudson River, and someone’s boarding pass from the flight, complete with a couple of smears from contact with the river water.

Sully and Skiles bade us farewell and headed over to the main terminal to catch flights home and the rest of us settled into the DC-7B for the evening flight back to Miami. At the holding point, the cowling for engine no. 3 (right inboard) was shaking and word from the cockpit was, we’re checking it out. After a few minutes we lined up and took off, but as we left the ground the engine failed and started streaming smoke and spilled oil.

Our outbound turn was instead a turn to go downwind, and only a couple of minutes later we were landing. The fire brigade had given us a water cannon salute after our first landing earlier that day, and now they were out again for us, this time for real. The landing was uneventful and we taxied back to the same parking stand as before. The oil that was dripping from the engine had metallic particles in it; the Wright R-3350 Cyclone engine was toast. A replacement costs $250,000, so the hasn’t moved since, another addition to the Carolinas Museum collection.

So that’s my story of US1549 and meeting the pilots a year later. Oh one last thing. The movie by Clint Eastwood is nonsense, he’s very right wing and used his anti-government agenda to smear the National Transport Safety Board as clipboard wielding cowardly bureaucrats to fill out the story to movie length. Sully and Skiles’ didn’t have a hope of getting back to the airport or any other runway and this was known at the time. The NTSB does incredible work solving accidents and making recommendations that save lives worldwide.

Happy anniversary to a great day for the airline business and 155 lucky souls.